Korea's economic growth has been based on export expansion. Among the various policies have been promulgated to increase Korea’s exports, the duty drawback scheme is a system under which customs duties and other taxes levied on imported raw materials can be refunded after they are used to produce export goods. It is one of several export incentives that are being used to increase the international competitiveness of exports. It alleviates the burden of tariffs levied on raw materials for the production of export goods.

Since the launch of the World Trade Organization (WTO) system, government support for exports has been restricted. The duty drawback scheme is an export incentive that is not regarded as a prohibited export subsidy, as long as the amount of duty drawback does not exceed the threshold level. Therefore under the current WTO system, it is one of the major export incentives allowed to the WTO members.

This paper examines the effectiveness of the duty drawback system in the promotion of exports in Korea by revealing the time series properties of the concerned variables in export demand. The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 presents an overview of the duty drawback scheme. Section 3 explains the previous literature and introduces the model that examines the effectiveness of the duty drawback scheme in export demand. Empirical evidence is shown in Section 4. Section 5 presents the conclusions and implications of this research.

Ⅱ. General Review of the Duty Drawback Scheme

1. Overview of the Duty Drawback Scheme

A duty drawback is the refund of duties paid on imported raw materials for export when they are exported by an exporter or producer of export goods. The duty drawback system allows exporters price competitiveness in foreign markets without the handicap of the duty paid on imported merchandise. This system is designed as one of the measures of export promotion.

Before July 1, 1975, raw materials were imported duty-free on the condition that they would be used to produce export goods. This practice had the following major defects in operation. With the increase in the domestic economic scale and the increase in domestic transactions, it became very difficult to post-manage duty-free goods after their clearance, and the tracing and confirmation of the use of all duty-free raw materials became almost impossible. To resolve this problem, the drawback system was adopted and has since been in operation.

The duty drawback system, which removes the burden of tariffs on exports, is intended to increase the price competitiveness of export goods. By utilizing this system, exporters may reduce production costs and, consequently, increase profit levels. Unlike the previous scheme allowing duty-free import of raw materials conditional upon use of those to produce export goods, customs administration may significantly reduce the transaction cost. Korea's duty drawback system has been used from July 1, 1975, based on the Special Act for Duty Drawbacks in Korea. Since July 1, 1997, the Korea Customs Service has been operating the automated drawback system and issuing paperless refunds. All the necessary procedures for drawbacks, including applications and actual refund payments, are computerized (Jung, 2006; Park, 2010).

2. Status of Duty Drawbacks under the WTO

The WTO system can be characterized by tighter regulation of the government's direct support and direct government support has actually decreased. Contrary to this, since its launch, the regulation of the indirect support of exports has been relatively weak; therefore, the indirect support approach has been emphasized by the members since the inauguration of the WTO system.

Paragraph 1.1 of the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures of the WTO says that a subsidy shall be deemed to exist if "there is a financial contribution by a government or any public body within the territory of a member". A subsidy is defined as the extension of financial support or income or price supports by the government or public institutions in the territory of the member state.

Paragraph 1.3 of the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures says that, except as provided in the Agreement on Agriculture, the following shall be prohibited: subsidies contingent, in law or in fact, whether solely or as one of several other conditions upon export performance, including those illustrated in Annex I. There are examples of regulated export subsidies in Annex I. The illustrative list of export subsidies in paragraph (i) of Annex I of the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures of the WTO shows an expression that says that the WTO has explicitly permitted a duty drawback that does not exceed the amount of the import duty that was actually levied on the imported products. Thus, the duty drawback under the WTO system can be regarded as an export incentive that is not included in the regulated export subsidies, as long as the refunded duty on imported inputs does not exceed the threshold level. Since, unlike direct export subsidies such as taxes and financial support directly targeting export promotion, duty drawbacks are not strictly controlled; many members of the WTO system actively utilize them to promote exports.

3. Operational Status of the Duty Drawback Scheme

The current average tariff rate in Korea is recorded as 11.2%. The rate is 41.6% for agriculture, 10.1% for the textile and clothing industry, and 8.0% for vehicles, for instance. A previously paid duty on imported goods makes exporters less competitive. Therefore, the refund of the duty paid on an imported commodity for its re-export after its manufacturing may have a positive influence on exports by lowering the burden on the costs of exporters and raising the profit level. Duty drawback schemes are thus expected to have a positive impact on exports.

In 1975, the proportion of duty drawback/total tariff revenues was as high as 153%. The proportion of duty drawbacks in import tariff revenues in Korea, compared to that in leading foreign countries, was relatively high. That is, although it was 2.9% in the United States in 1998 and 2.1% in 2001 in the United States (Song, 2005), and 0.5% in Japan in 2001 (Lee, 2008), it was 35% in 1998 and 25% in 2001, respectively, in Korea. In 2009, the amount of duty drawbacks in Korea was 3.234 trillion won, while the amount of tariffs levied amounted to 14.961 trillion won. The proportion of duty drawbacks in the total tariff revenue was 21.6%, which was notably high.

The proportion of customs duty refunds in the total levy in Korea is higher than that in major countries, perhaps due to the structure of the Korean export industry. The structure of the Korean export industry can be characterized by trade processing, which means importing raw materials and re-exporting them after manufacturing exportable goods. It is important to know the proportion of duty drawbacks in the total tariff revenues because such proportion is very high in the Korean economy.

Although the share of duty drawback/export values was 11.3% in 1976, 4.7% in the 1980s, 1.4% in the 1990s, and gradually fell to 0.7% in the 2000s, the ratio of net profits to net sales in Korea, was 0.7% in the 1990s (Choi, 2003), and 0.01% (BOK, 2003) in 2001. Since the net profit ratio has been fairly low, the provision of duty drawbacks to exporters may significantly contribute to export promotion.

Chao, Chou and Yu (2001) used data for the duty drawback scheme of China and examined its effect on exports. According to the study of Cadot, Melo, and Olarreaga (2003), duty drawback systems are often justified in the sense that they tend to correct the anti-trade bias imposed by high tariff levels. Also, duty drawbacks are eliminated on intra-regional exports, which will in turn lead to lower tariffs for goods used as inputs by intra-regional exporters.

According to the study by Jung (2007), the duty drawback system has had a positive effect on exports rather than a negative effect on exports. For this reason, the existence of reimbursement costs and their negative effects on exports have been interpreted.

According to the study of Mah (2007a), the duty drawbacks implemented by the Chinese government has affected export supply in China. The estimation was conducted with the ordinary least square method using the first differenced data. He showed that the duty drawback system implemented by the Chinese government did not contribute to export promotion in China.

Using annual data from 1975 to 2001, Mah (2007b) tested whether or not the duty drawback system of Korea has promoted Korea's export supply. The results of the study showed that relative prices and domestic demand pressures did not significantly affect the export supply, but that the duty drawback was significant in explaining the export supply of Korea. Thus, only a few rigorous attempts have been made so far to empirically reveal if the duty drawback scheme has actually been effective in the promotion of exports.

The current study analyzes the impact of duty drawbacks on Korea's exports using an export demand equation. Estimating export demand functions using the elasticity approach to analyze price changes calls for analyzing the factors affecting export demand. Since the demand for and supply of each good depends on its price, it is assumed in the analysis that relative price changes affect the direction and extent of exports. The current study is different from Mah(2007b) in the sense that, first, although Mah(2007b) considers export supply, equation (1) in the current study uses an export demand function; and, second, the current study applies a small sample cointegration test, thinking of the limited number of observations.

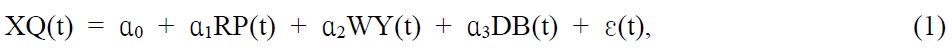

For the foreign demand for Korea's exports, foreign income, relative price indices, and duty drawbacks can be regarded as the determinants. Each variable appearing in the export demand equation takes a natural logarithm, which is shown as follows:

where XQ represents Korea's export value, and RP represents the relative price index, that is, the foreign wholesale price index divided by Korea's export price index. WY is a variable that represents world income. There are certain limits in calculating the foreign wholesale price index and the value of world income. Therefore, the percentage of the shares of Korea's six major export partners USA, Japan, China, Britain, Germany, and Taiwan are considered in calculating the weights. DB denotes the amount of duty refund, which is measured in US dollars using an average exchange rate.

The annually observed data for Korea's exports, foreign wholesale price index, Korea's export price index, and GDP are taken from the Bank of Korea’s Economic Statistics System. The data for the amount of duty drawbacks are drawn from the Korea Customs Office’s

The estimated coefficient of α1 can be interpreted as the relative export price elasticity. Its sign is in general expected to be positive, since an increase in the foreign price level would raise demand for Korea’s exports. However, if, assuming a constant foreign price level, a rise of export price as much as 1% leads to a reduction of export quantities by less than 1%, export values would rise. In that case, α1 may have a negative value. α2 can be interpreted as the world income elasticity. Its sign is expected to be positive, since an increasing world income level is expected to increase Korea's exports. The estimated coefficient of α3 can be interpreted as the duty drawback elasticity. Its sign is expected to be positive, since the provision of duty drawbacks would lead to the higher price competitiveness of exporters in Korea.

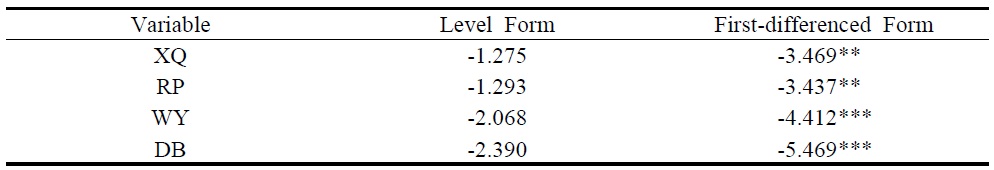

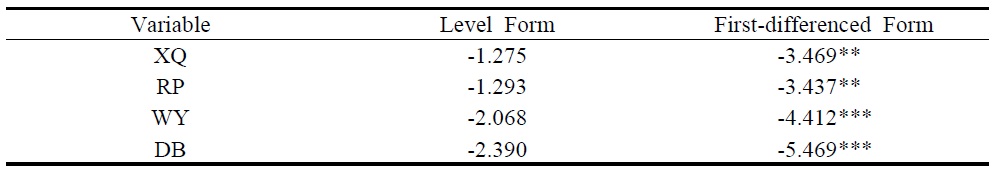

The augmented Dickey-Fuller test is applied to the concerned variables appearing in equation (1) to test their stationarity. The results reported in Table 1 show that the levels of the concerned variables are not stationary at any reasonable level of significance, but the first differenced forms of all the concerned variables are stationary at a 5% level of significance. Therefore, all the variables are assumed to be integrated of order one.

[Table 1] Augmented Dickey-Fuller Unit Root Test Results

Augmented Dickey-Fuller Unit Root Test Results

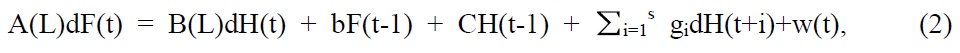

Since the concerned variables are assumed to be integrated of order one, the cointegration test is applied to examine whether or not they have long-run equilibrium relationships. Since the number of observations for each variable is limited to 34 in this paper, the small sample cointegration test proposed by Banerjee, Dolado, and Mestre (1998) is used. It depends on the statistical significance of the estimated coefficient of the lagged dependent variable in an autoregressive distributed lag model augmented with the leads of the regressors. The t statistics of the coefficient of the lagged dependent variable, tb, is obtained from the following equation:

where F, H, and w are the regressand, the vector of regressors, and the conventionally assumed error term, respectively. The vector H consists of RP, WY, and DB. L and d denote the lag operator and the differenced form of the concerned variable, respectively. According to Banerjee, Dolado, and Mestre (1998), s = 1 or 2 in equation (2) would guarantee good size properties. The cointegration test results that are based on the tests of Banerjee, Dolado, and Mestre (1998) depend on the calculated t statistics of the OLS estimate of the parameter b in equation (2). Under the null hypothesis of non-cointegration, b is equal to 0, but under the alternative hypothesis of cointegration, -2 < b < 0.

The estimated tb statistics for two (one) lead(s) of s in equation (2) when XQ is used as the regressand are found to be 0.497 (1.073). Since they are smaller than the critical value at the 5% level of significance, -3.89, in its absolute value regardless of the number of leads, the null hypothesis of non-cointegration is not rejected. That is, the variables in equation (2) appear not to be cointegrated. Therefore, this paper applies the OLS estimation using the first differenced variables. The estimation results are reported in Table 2.

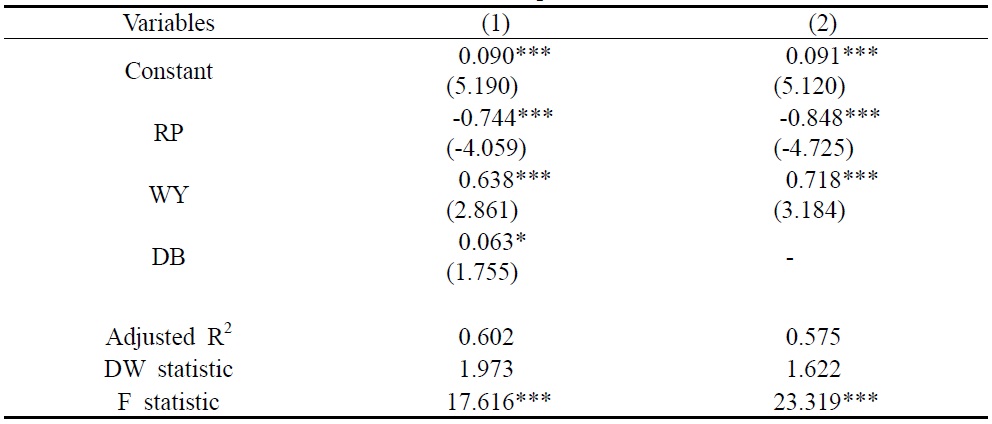

[Table 2] Results of the Estimation of the Export Demand in Korea

Results of the Estimation of the Export Demand in Korea

The estimated coefficient of the relative price index is revealed to be negative and statistically significant even at the 1% level of significance. As was explained before, this would be explained in the sense that export quantity will not respond sensitively to a rise in the export price index. The estimated elasticity is revealed to be about -0.8.

The estimated coefficient of the world income is revealed to be positive and statistically significant at the 1% level of significance. The elasticity is calculated to be between 0.6 and 0.9. The estimated sign is consistent with the

The estimated coefficient of the duty drawback is shown to be positive and statistically significant at the 1 or 10% levels of significance, as expected. The duty drawback elasticity is calculated to be about 0.06 ~ 0.11. That is, the results in Table 2 show that a 10% increase in duty drawbacks would increase demand for Korea’s exports by 0.6 to 1.1%. Therefore, one can say that the duty drawback system of Korea has significantly contributed to export promotion.

A duty drawback is the refund of tariffs paid on importing raw materials used in producing export goods. It is a common export support system within the regulations of the WTO Subsidies Agreement. Under the WTO system, the duty drawback system is an export incentive that is not included in the list of prohibited export subsidies, for as long as the duty on imported inputs does not exceed the threshold level. According to the current WTO rules that regulate direct government support, the regulation on indirect support is relatively weak. Therefore, WTO members may actively utilize the duty drawback system to promote exports.

The current study reveals the effect of the duty drawback system in the export demand of Korea, using the relative price index of Korean exports (Korea's export price index divided by the foreign price index), world income and drawbacks such as the factors explaining the export demand of Korea over the period 1975-2009. The ADF unit root test shows that all the concerned variables are integrated of order one. The results of the small sample cointegration test of Banerjee, Dolado, and Mestre (1998) show that the concerned variables are not cointegrated, and as such, the current study provides the OLS estimation results using the first differenced forms of the concerned variables.

The estimated results of the current study are, in general, consistent with the expectation. The duty drawback is revealed to have a positive and significant effect on Korea's exports. The duty drawback system, which is available as an export incentive under the WTO system, is shown to be a very useful policy instrument to take advantage of.