When it came to admiring the view around the walled city of Pyeongyang and the Daedonggang River in pre-modern Korea, Bubyeongnu Pavilion 浮碧樓 and the Yeongwangjeong Pavilion 練光亭 constituted the first famous scenic sight that was mentioned. Pyeongyang’s Bubyeongnu Pavilion, which North Korea has reportedly designated as its national treasure no. 17, established its name as one of the top three pavilions of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) along with Yeongnamnu Pavilion 嶺南樓 in Miryang and Chokseongnu Pavilion 矗石樓 in Jinju. Bubyeongnu Pavilion is said to have been built as part of the annex building to Yeongmyeongsa Temple in the times of the Goguryeo Kingdom (B.C. 37–A.D. 668). The history of Yeongwangjeong, also a well-known attraction and national treasure no. 16 of North Korea, can be traced back to Goguryeo, when the walled city of Pyeongyang was first being built. During the Joseon era, aristocrats readily used the two pavilions to hold literary or artistic gatherings to enjoy music or art. This tradition was discontinued for over 70 years due to the division of the Korean Peninsula.

The kings of the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392) would occasionally go sightseeing and tour Pyeongyang with their subjects. They especially enjoyed watching the outdoor performances and boating at Bubyeongnu and its vicinity. Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong were one of the best-known places to be frequented by the kings.

In terms of pavilion architecture, Bubyeongnu and Yeongwagjeong both feature unique structures. Hong Gyeongmo (1774 –1851) said that “Yeongwangjeong is like a beautiful woman in light makeup, seated behind a beaded curtain, while Bubyeongnu is like an ascetic in rough hemp clothes but with a remarkable presence.” Hong summed up Yeongwangjeong and Bubyeongnu as “beauty and splendor” 佳麗 and “absolute pureness” 淸絶, respectively.

Among previous studies looking at historically significant sites of beauty in the Pyeongyang region, one research focused on the exchanges that took place at Bubyeongnu between central and local literati (Jang 2014). The study diachronically analyzed poetic exchanges to show how central and local intellectuals communicated at Bubyeongnu from early to late Joseon Dynasty. Participants included high-profile figures such as King Sejo 世祖 (r. 1455 –1468), Yim Je 林悌 (1549–1587), Yi Sihang 李時恒 (1672–1736), and Yi Mansu 李晩秀 (1752–1820).

The present article seeks to identify precisely how literary figures of the Joseon Dynasty shared and enjoyed the cultural landscapes of Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong. Whenever literati groups such as envoys came to Pyeongyang to stay for a while, local officials of Pyeongyang including the provincial governor would guide them to scenic spots and hold banquets for artistic enjoyment and pleasure. During these times, Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong were the locations of choice. Those who frequently traveled between Joseon and China wrote detailed descriptions of how they enjoyed the beautiful sights of Pyeongyang, especially the architecture such as Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong. Other literary figures who visited Pyeongyang for various reasons, such as visiting their acquaintances, also wrote appealing poems about their trips to the two pavilions. This article will thus analyze travel records and well-known poetry during then to understand how Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong captured the interest of the literati class. The findings of this article will lay the groundwork necessary to systematize how Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong were materialized into literary space in the time-honored tradition of writing poetry and prose in the presence of these two pavilions. This research will also contribute to vibrant discourse in the area of literary geography, which studies geographical names and space in the literary context.

Central Landscape of Route Entering the Walled City of Pyeongyang

Envoys heading to China reached Pyeongyang after leaving the capital city of Hanyang and passing regions including Pyeongsan, Seoheung, Bongsan, and Hwangju. The travel records by Joseon envoys to China contain descriptions of the first things they observed upon entering Pyeongyang. Their first impressions of Pyeongyang tended to be the moment they stepped into the walled city, after which they would get a full view of all the picturesque scenery around the city, including Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong, as if seeing it on one big screen.

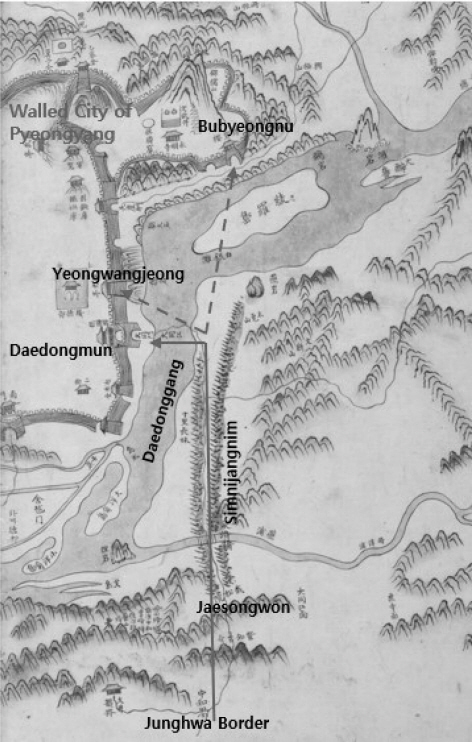

Travelers usually entered through the Pyeongyang City Administration, past the borders between Pyeongyang and Junghwa. Envoys would start writing about their experiences of Pyeongyang beginning from this point in great detail. Among others, the first things they usually started with were the Jaesongjeong Pavilion 栽松亭, otherwise known as Jaesongwon 栽松院, and the majestic sight of Simnijangnim 十里長林, which was a long forest stretching about 10-

The weather is clear. I traveled 50-ri to Pyeongyang and slept at Daedonggwan Guesthouse ···· Pyeongyang has the best of all rivers and mountains ( je-il gangsan 第一江山). This area continued to prosper for 5,000 years since the times of Dangun 檀君 and Gija (Ch. Jizi 箕子). No place can compete with Pyeongyang when it comes to the scenic site in this country. As I moved from Yeongjegyo Bridge 永濟橋 toward Daedonggang River, I saw a road along the Simnijangnim Forest on the south side of the river. The boat sailed with the wind. Flocks of waterfowl kept appearing and disappearing within the forest. At the end of the forest, a multi-colored pavilion and city walls cemented with lime towered over me, and its dimly lit features looked as if an actual painting had come alive, leaving me feeling quite refreshed in mind and heart. While looking around the place, my fingers pointing at the scene, I finally got onto the boat. The boat had a red rail and colored eaves with plaques hanging above. The left side read “Neungna beomga” (a boat floating in Neungnado Island 綾羅泛舸), and the right side read “Byeokan busa” (a raft floating to the Milky Way 碧漢浮槎). Then, I got off the boat, went past Daedongmun Gate 大同門, entered Yeongwangjeong 練光亭, and rested there.4 (emphasis mine)

Simnijangnim Forest came into view once one crossed Yeongjegyo Bridge past the border dividing the districts of Junghwa and Pyeongyang. A road was set between the long trails of Simnijangnim Forest and guided the envoys to the crossing point of Daedonggang River. To the delight of the travelers, one would occasionally catch a glimpse of birds flying through the trees of Simnijangnim Forest or boats riding the waves of the river. The Simnijangnim Forest ended at this point by the river, where travelers were granted a full view of the most famous landscape of Pyeongyang. The image of the high-rising city walls, the lime-cemented battlement, and the fashionably multi-colored pavilion sitting on top of it would have seemed like something out of a vivid painting. Heo Bong (1551–1588) mentioned the lime-cemented castle wall and pavilion building atop in his book

While many colorfully painted architecture such as the gate tower boasted their splendor, Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong were unrivalled in the attention they drew from people traveling the region. Below is a recreation using an old map of the route that officials such as Bak Saho and Heo Bong would have taken upon entering the walled city of Pyeongyang back then.

The literary work left by travelers show that the boat, which took people to the walled city of Pyeongyang from the river point where the view of Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong opened up, also left a lasting impression. High-ranking officials including envoys to China found the boats used for crossing the river just as attractive as the painted pavilions. According to officials like Heo Bong and Yi Haeeung (1775–1825), the boat was a “jeongjaseon” (a boat with a pavilion-like structure erected within 亭子船) with a rooftop decorated with grass. Carrying a plaque of its name, “Seungbyeokjeong” 乘碧亭, the boat could accommodate over 100 passengers and over a dozen strong workers in addition to maneuver the ropes.

Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong, standing high above the castle walls, would have provided a splendid and wonderous view to the travelers as they gazed at the walled city. This first impression of Pyeongyang likely aroused interest in the tour even further. Travelers would eventually decide that their first destinations be Yeongwangjeong and Bubyeongnu as soon as they entered the city and settled at their lodgings.

Panoramic View Formed by Two Complementary Pavilions

The first thing most of the visiting literati desired to do after crossing Daedonggang River, disembarking the pavilion-boat, passing through Daedongmun Gate, and entering the walled city of Pyeongyang was to visit Yeongwangjeong and Bubyeongnu. It was Yeongwangjeong, which was close to Daedongmun Gate, that particularly attracted visitors first starting from the moment they crossed the river. Scholar-officials like Yi Haeeung or Bak Saho would recount the literary works left by renowned authors that imbued the structure with historical significance. Various literary works received their attention, such as the plaque saying “Je-il gangsan” (the best of all rivers and mountains 第一江山), which was written by Zhu Zhifan 朱之蕃 (1555–1624), a royal messenger from Ming China to Joseon, and a verse couplet written by the Goryeo poet Kim Hwang-won 金黃元. The wall also displayed plaques of other poems written by well-known literary figures such as Jeong Jisang and Kim Chang-heup.

The biggest interest of the visitors, however, was the role Yeongwangjeong played in their enjoyment of the surrounding landscape.

Heo Bong described the characteristics of the landscape surrounding Yeongwangjeong while narrating its history and location. The following is what he wrote upon climbing up to the pavilion:

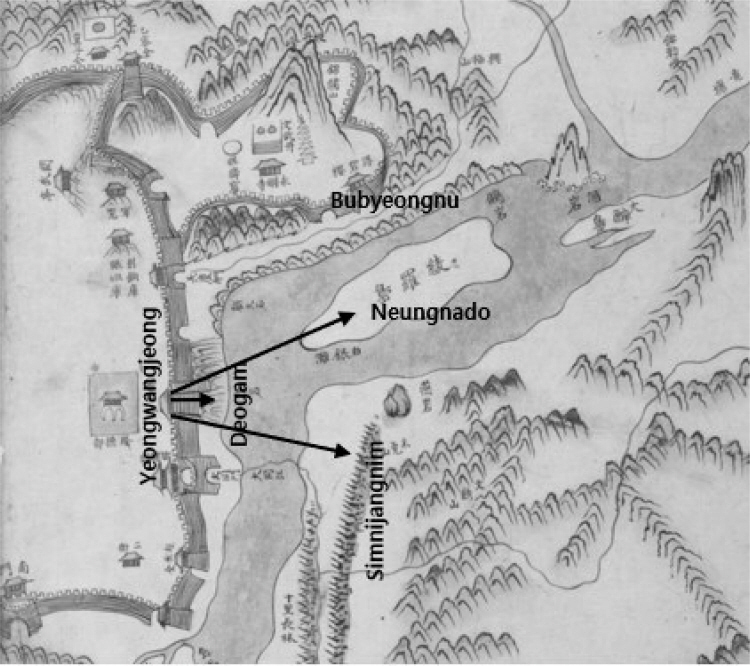

I went inside the city walls and up to Yeongwangjeong Pavilion. Since Yeongwangjeong presses down the top of the city walls and the rock beneath it pushes down on the intense rapids below, people of Pyeongyang considered this act good and named the rock beneath as Deogam (Virtuous Rock 德巖) for suppressing the rapid waves. Yeongwangjeong was built by the state councilor Yi Gyemaeng 李繼孟 (1458–1523). Initially, the place was built as a thatched pavilion. Later, Hong Shin 洪愼 and Hong Yeon 洪淵, who were father and son, happened to be appointed as the deputy magistrate of the same region in succession. They continued to polish and adorn Yeongwangjeong until it became the magnificent architecture it is now. The view of the pavilion is best at night, when all three sides of the pavilion are surrounded by nothing but blue waves. Since the blue waves illuminate just like the sky, from a distance it seems as if a broad layer of silk spreads wide over the vast and boundless fields. From above, the space below is so utterly light and clean that it is impossible to make out where it begins and ends. It is hard to express in words whether it is the pavilion or the waves that stands high above the air up there.9

Heo Bong mentioned Yeongwangjeong, which soared above the city wall, and Deogam rock beneath, which stood against the harsh waves of Daedonggang River. He then described Yeongwangjeong’s exceptional location in great detail: the waves of the Daedonggang River that embraced the three sides of Yeongwangjeong, the light from the sky reflected by the river, and the indescribable beauty of the river that looked like silk spread out when gazed from afar. While Yeongwangjeong alone would have been enough to elicit a stream of compliments, Heo Bong wished to underline the beauty of the overall landscape seen from above, which further amplified the pavilion’s value and meticulously captured the details of its surroundings.

Yeongwangjeong was frequently used as lodgings for the envoys visiting during the winter.

The fog, which started at dawn, finally lifted after many hours. I stayed here for the day. After washing my face at the break of dawn, I opened all eight windows and looked down at the river flowing before me. The early morning mist had spread toward the riverside, and women were washing silk clothes. That, too, was a scenic sight to behold. The wind started to blow as the day grew dark, clearing up the cloud and mist. I stood up and took in the view around me as I roamed around. The painted fence of the pavilion closely adjoined the city walls, making it look like it was floating in the air. The wave of the big winding river sparkled like silk. From the wild geese quacking on dunes to the mountains sitting sporadically across the field like dots from afar, just about every color presented by the nature was refreshing and beautiful. The place did not earn the reputation as “the best of all rivers and mountains” 第一江山 for nothing.10

Prince Inpyeong was able to get a full picture of what was written on a plaque at Yeongwangjeong—“the best of all rivers and mountains”—by seeing the actual sight with his own eyes. Looking at the autumnal scenes outside Yeongwangjeong, the prince could appreciate the unique spatial quality of the pavilion. Being well-versed in paintings, he captured both the morning and evening views from Yeongwangjeong. In the morning, the wet fog and women washing clothes at the riverside came into his view. The evening provided a scene cleared of clouds and mist. Seeing that the railing of Yeongwangjeong was built quite close to the city walls, the prince was hit with a rare feeling of hanging in the air. He also absorbed other scenes, including the glittering flow of Daedonggang River, wild geese quacking on the sand, and the mountains rising high across the field. To Prince Inpyeong, the views form Yeongwangjeong let him fully take in the rich beauty of the season.

Bubyeongnu Pavilion was also considered a great space to take in the nearby landscape and appreciate its beauty. Like from Yeongwangjeong, the visitors were impressed by the river and mountains stretching out in front. The following is a record by Yi Euibong, who was part of a group of envoys in the late 18th century.

When you step down from Juangnu Pavilion 奏樂樓 and go up to Bubyeongnu Pavilion after climbing dozens of stone stairs, you will be looking down on a flat island that boasts peculiar views while a long wide river drinking in the vast energy of the sea flows right beneath you. This, added to the scene of the high mountain tops appearing sporadically one by one on the east and south and running through the winding path, will put the paintings of Wang Mojie (王摩詰, 618–907) to shame even if he is reborn.11

Yi Euibong felt as if he was staring at a vivid landscape painting as he gazed upon the Daedonggang River down from Bubyeongnu, the Neungnado Island that spread out wide and flat in the middle, and the high mountain peaks standing far away in the east and south. In this way, Bubyeongnu was regarded as another remarkable spot to enjoy the surrounding landscape.

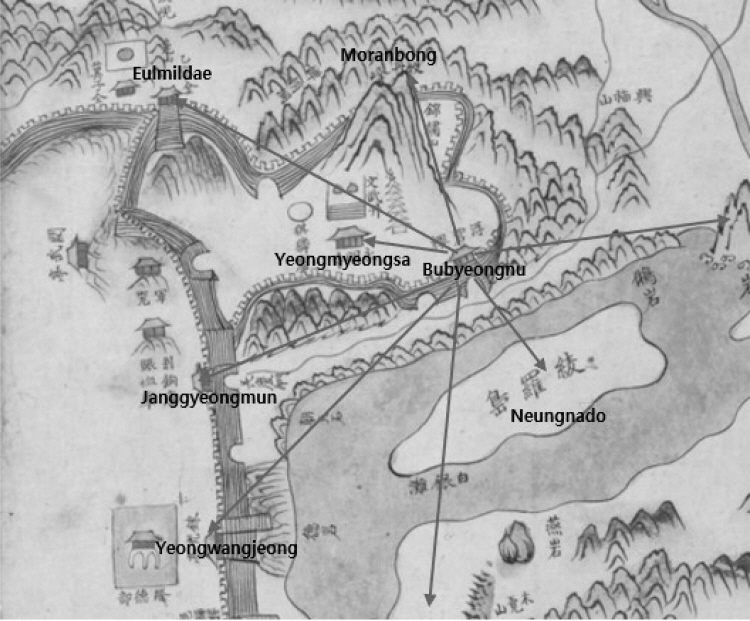

The natural and manmade landscape forming its surroundings were mentioned more diversely in regard to Bubyeongnu compared to Yeongwangjeong. Heo Bong’s

① I went to Bubyeongnu because the provincial governor, who had gone earlier, summoned me there. Outside Janggyeongmun Gate 長慶門, stiff cliffs were standing before me like a folding screen. O Hi-maeng 吳希孟 named the cliffs Cheongnyubyeok 淸流碧. I reached Bubyeongnu after walking 3 to 5-ri (approximately 1.6 to 2.7 km) along the wall. The pavilion was situated south of Yeongmyeongsa Temple 永明寺, which was also the old site of King Dongmyeong’s 東明王 (B.C.37–B.C.19) Gujegung Palace 九梯宮. There were two bridges, Cheongungyo 靑雲橋 and Baegungyo 白雲橋, with neat staircases that looked like they were newly built. All these remains are said to have been passed down since the times of King Dongmyeong. Although I have also heard that Giringul Cave 麒麟窟 and Jocheonseok Rock 朝天石 lie within, such is all but absurd. Writers and poets may have written songs and poems about them, but they are nonsensical stories that are hardly worth a glance. Since this building [Bubyeongnu] is not a double-storied structure, some called it Bubyeokjeong 浮碧亭.12 Behind the pavilion stands Moranbong Peak 牧丹峯, and in front, a large river flows around it. The river divides into two parts in front of the pavilion, and at its center lies Neungnado Island 陵羅島. From a distance, one side of a silk window is half exposed between the cliffs. This is Yeongwangjeong. Pine trees and cedar trees stand thick and dense, stretching seemingly endlessly as far as one can see. This is Jaesongjeong 栽松亭 and Jangnim Forest 長林. In the east, Juam Rock 酒巖 rises high above the waters, its form resembling a crouching tiger. In the west stands Eulmildae Pavilion 乙密臺 high up in the forest, seemingly flying in the air, and every part of feature at its left, right, front, and back looks quite odd and mysterious, which offers a sight truly gifted by the heavens. The view of the pavilion is the best in the east. Although I have toured many places, I have never seen a view quite like this. On the east side, another building called Hambyeokdang 涵碧堂 awaits, its serene and exquisite look stealing my heart. The provincial governor held a banquet, placed a white target board at Neungnado Island, and arranged for military officials to pair up and conduct arrow-shooting session. They also prepared food for the feast. Artistic activities such as Pogu Ball Dance 抛球, Hyangbal Cymbal Dance 饗鈸, Mudong Dance of Young Boys 舞童, and Mugo Drum Dance 舞鼓 sounded even louder and noisier than yesterday.13

② The Bubyeongnu Pavilion stands firm and high outside Janggyeongmun Gate, inside Jeongeummun Gate 轉錦門, and east of Yeongmyeongsa Temple. The waves of the river slap against the city walls while the surrounding rock soars up into the sky. Behind the pavilion stands Moranbong Peak; in front lies Neungnado Island. The front pillar of Bubyeongnu Pavilion displays a rhyming couplet that reads “A silent shadow sinks within the jade-green light” 靜影沉璧, “while the brightness in the air gushes out in gold” 浮光躍金. When it comes to beautiful and clear views, this pavilion tops all other pavilions in the country. Looking from the east, Jocheonseok Rock touches the blue sky while Eulmildae Pavilion sits across Sonammun Gate 小南門 and is enclosed by the battlement. At the center sits a roundish burial mound called the Grave of Eulmil 乙密. The townspeople made it into a sacrificial ground for the mountain god. We returned to our lodgings, drunk, when it grew dark, past the Deugwollu Pavilion.14

The first quotation ①, by Heo Bong, gives a detailed account of Bubyeongnu as a perfect place to view the colorful and diverse landscape of the region. The second quotation ②, by Yi Haeeung, lists several surrounding spots to emphasize how fitting Bubyeongnu is for enjoying the wonderful view. Both accounts put together form the following scene: climbing up to Bubyeongnu and taking in the surrounding scenes left and right looking toward the Daedonggang River gives a breathtaking view of the city gates, including Janggyeongmun and Jeongeummun, and gate towers such as Deugwollu Pavilion. Jocheonseok Rock, Juam Rock, Neungnado Island, and other scenic landscapes mingle with the forever-moving waves of the Daedonggang River. Turning away from Bubyeongnu to view the castle inside provides a view of Yeongmyeongsa Temple, Moranbong Peak, and Eulmildae Pavilion. Heo Bong stressed how the line of sight could go on forever when looking at the Daedonggang River to the right. The silk-draped window of Yeongwangjeong can be seen about 5-

The spots in the quotations above can be understood as separate entities as well as one wide panoramic space formed by connecting them. Bubyeongnu lay at the center of the remarkable view that could be appreciated from the route traveling southeast to northeast of the city. As Heo Bong mentioned, installing a target board at Neungnado Island and having people shoot arrows down toward it from Bubyeongnu was one of the specialties of the Bubyeongnu tour.

Yi Haeeung, deeply touched by the unique view at night while looking around Bubyeongnu and Cheongnyubyeok Cliff, expressed his sentiment through a poem in his travel records.

Candlelight burns bright and clear late at night at Bubyeongnu, Creating a reversed rainbow at a river ahead. As I climb up and up toward Cheongnyubyeok Cliff, almost 100-cheok high, It feels like flying in the air, mounted on a whirlwind.15 (Yi Haeeung, “Cheongnyubyeok Cliff”)

As the poem above shows, Yi Haeeung reached Bubyeongnu after climbing up towards the high-risen Cheongnyubyeok Cliff. Rather than feeling out of breath, he felt a sense of ecstasy, as if riding on the wind and soaring to the heavenly world. The trail of sparkling lanterns that lit the Bubyeongnu area as the night wore on was another factor that lured visitors like Yi Haeeung to Bubyeongnu. Merely lighting up Bubyeongnu gave birth to another beautiful sight as the lanterns’ reflection on the waters of Daedonggang River formed another aesthetic view. The poetic experience of the night view was possible only by touring Bubyeongnu.

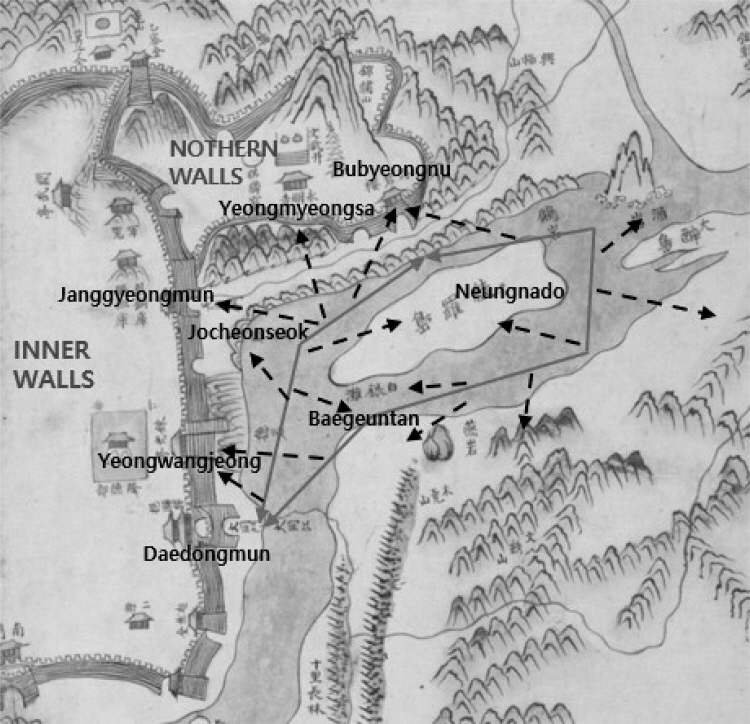

Main Route for Boat and Sleigh Rides

Literati who visit Pyeongyang from the capital city of Hanyang would first enter the city walls through Daedongmun Gate. After choosing where to stay among the buildings of Seonhwadang 宣化堂, Yeongwangjeong, Yuhyangso (Local Advisory Agency 留鄕所), Daedonggwan 大同館, they would then go out to enjoy the famous landscape. One way to enjoy the view was to go boating. They would depart from Yeongwangjeong, which was in the vicinity of Daedongmun Gate, and arrive at Bubyeongnu, next to the Jeongeumun Gate, while admiring the scenic sights around them. Daedongmun was the eastern gate of the inner walls of Pyeongyang, and Jeongeumun was the southern gate of the northern walls of the city, which was located northeast of Yeongwangjeong. When the river froze in the winter, people would replace the boats with sleighs.

Whether by boat or sleigh, the literati touring the route from Yeongwangjeong to Bubyeongnu could take in the view from below the city walls as they looked up at the buildings and the surrounding landscape. There were natural landscapes, such as the enormous rocks of Deogam and Jocheonseok, and artificial landscapes, such as architectures like Bubyeongnu, Yeongwangjeong, and Yeongmyeongsa. They would take in views of Neungnado Island, which lay in front of the Bubyeongnu, and also drown themselves in the mystic mood of the waters as the boat sailed through the waves of Daedonggang River. Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong was not only a place that offered pleasurable views of the exquisite landscape but also an excellent background for boating and sleighing.

In 1731, the literatus Hwang Taek-hu (1687–1737) recited the poem below during his boat ride from Yeongwangjeong to Bubyeongnu while accompanying Yi Jongseong 李宗城 (1692–1759), the royal censor of Pyeongando Province, to Pyeongyang.

Little by little, a boating song spreads. Clear weather lifts the cloud and mist on the river. Loud splashing sounds resonate on a sandy island where silk is being washed, A rocky site where a fishing rod is cast displays a deep green hue, the color of a willow. Everything that jumps to my eyes is a recipe to write a poem, Here we raise our wine cups even when we are in the Northwest. By the time the temple building looks even brighter, We shall take a seat and wait till the sound of the evening bell.16 (Hwang Take-hu, “Going Upstream from Yeongwangjeong to Bubyeongnu”)

Yeongwangjeong and Bubyeongnu served as an essential background to Hwang Taek-hu’s boat ride along Daedonggang River. The poem tells how the cloud and mist rolled away as they moved along on a boat, opening up the idyllic scenes around them. Hwang Take-hu slowly immersed himself into the poetic experience while listening to the sounds of water on Neungnado Island and gazing at the willow trees nearby the Cheongnyubeok Cliff. The poem also describes how he waited for the sound of the evening bell while looking towards Yeongmyeongsa Temple, where Bubyeongnu Pavilion was. The lines show that he has fallen even deeper into a tranquil and sentimental mood.

Yi Deok-mu (1741–1793), another late 18th-century literatus of Joseon, savored the atmosphere of the spring through the sight of ripening barley as he gazed at Bubyeongnu from a boat.

Rounding the side corner of Bubyeongnu, I can vaguely make out the red pillars. Encountering white herons roaming about at a leisurely pace I imagine a dragon that lives in quiet peace. While the rising tide continuously rolls into the lonesome castle, the flapping sail is completely soaked with rain. Gazing at the fresh green barley of Neungnado Island, I pause my rowing for a second to behold the hard-working farmers with envy.17 (Yi Deok-mu, “Seasonable Rain Showers While Gazing at Bubyeongnu from a Boat”)

This undated poem shows how the boating trip presented a lively picture of spring around Bubyeongnu. When Yi Deok-mu took a boat from Yeongwangjeong and went around the corner by the river, the first thing he noticed from afar was the hazy red pillars of Bubyeongnu. His eyes then moved to the scenic site below the pavilion. He saw white herons wandering leisurely and the waves rising beneath the cliff due to the incoming tide. He also noted a barley field wholly soaked by the spring shower. Finally, he appreciated the scene of farmers at Neungnado Island with hopes of their fresh new barley. To Yi Deok-mu, Bubyeongnu served as the background of boating that enrichened the bountiful sight of spring.

Hong Yangho (1724 –1802) also went boating from Yeongwangjeong up to Bubyeongnu when he was appointed Governor of Pyeongando Province in 1791.

Floating on a boat along Daedonggang River like an immortal god, The drizzle stopped, and the sunset began. The brightest moon of the year rises above past the day of the full moon. As the fresh wind blows at night, the time has come for the flow of the Big Fire star 大火. The fantastic scenery of Giringul Cave rivals that of Chibi Red Cliff 赤壁, The jade bamboo flute of the present follows the line of Su Zizhan’s 蘇子瞻 excursion. As we row on the moonlight reflected on the river, we see the Milky Way swaying beneath, Every manifestation of nature floating on the deep river stretches vast and endless.18 (Hong Yangho, “Going up Daedonggang River Towards Bubyeongnu on the 16th Day of the 7th Month”)

Hong Yangho went on an excursion to Bubyeongnu on the sixteenth day of the seventh lunar month, knowing that it was precisely the same day Su Shi 蘇軾 (1037–1101) of Song China wrote “Chibi Fu” 赤壁賦. Traveling from Daedongmun Gate to Bubyeongnu, he felt honored to experience what Su Shi had as well. He gazed at the bright moonlit river as he listened to the jade bamboo flute play. His boat passed Cheongnyubeok Cliff, where Giringul Cave was. The route from Yeongwangjeong to Bubyeongnu felt ideal to feel the atmosphere of the autumn night. He had already visited the place thirty years ago, in 1763, while serving as the magistrate of Uiju, Pyeongando Province. He had taken the same route and written a poem titled “I Went up Bubyeongnu Along with the Deputy Envoy, Took a Boat Down to Daedongmun Gate, and Went East Across the River.”

Seo Yeongbo (1759–1816) also wrote a related poem in 1796, when he was thirty-eight years old, after traveling from Daedongmun Gate to Bubyeongnu, past the Baegeuntan Rapids 白銀灘. He wrote down his sentiments on the boat ride back to Daedongmun after enjoying a drink at Bubyeongnu.

Meanwhile, sleighing offered a different kind of delight to the literati as they glided through the frozen rivers connecting Yeongwangjeong and Bubyeongnu during the winter season. Yi Euibong, who was part of the group of royal envoys to China, rode a sleigh to the frozen Daedonggang River. He went from Daedongmun Gate near Yeongwangjeong to Jeongeummun Gate and walked around Bubyeongnu and Yeongmyeongsa Temple. It was the morning of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, 1760.

The weather was cold and clear.... I felt jolly, as if I could fly, taking off on a sleigh, leaving my horse behind at Daedongmun Gate. The sunlight finally came through right at that moment, and when it shone down on the icy ground, I could see the shadow of the mountain and the movement of the water beneath flickering on the hem of my clothes. Watching the pavilions and castles around me, I felt as if I had entered a crystal world.... After returning to the Yeongmyeongsa Temple, I went to Jeongeummun Gate and rode the sleigh again. In a blink of an eye, I reached Daedongmun Gate, where my horse was already waiting for me.22

Despite the cold weather, the sleigh ride brought Yi Euibong no less joy than the boating experience. As the sleigh took off, he immediately felt cheerful. The morning rays of the sun reflected off the frozen lake, while the pavilions and castles made him feel as if he were inside a magical crystal world. All these were described as a particular delight attainable by admiring the scenery from the side of the walled city while gliding upwards from Yeongwangjeong to Bubyeongnu.

Jo Hyeonmyeong 趙顯命 (1690–1752), one of the literati during the early 18th century, wrote a poem about his experience going up Bubyeongnu on a sleigh.

After riding on an armored horse, banners busily flapping all morning, The music heard from the sleigh at night sounds slow and leisurely. While all kinds of fish remain quiet underwater, The moon and the stars are in full glow right above our heads. Bubyeongnu over there looked dreamy in the distance, Then suddenly, I find Neungnado Island standing right before me. As I advance to the red railing, the singing and dancing starts, With a pretty girl coming around to pour me red pine pollen wine.23 (Jo Hyeonmyeong, “Towards Bubyeongnu on a Sleigh up a Frozen River One Moonlit Night”)

One cold, bright winter day, Jo Hyeonmyeong went out to enjoy a sleigh ride. He seems to have left from Daedongmun Gate near Yeongwangjeong. This route would have provided a view of Bubyeongnu in the distance. Despite the freezing weather, he describes having a splendid time at night. While gazing dreamily at Bubyeongnu lighten up afar by the rays of the moon and stars, he was surprised to reach Neungnado Island before he even knew it. The poem shows how he considered his swift arrival at the island and Bubyeongnu on a sleigh a novel experience. He ends by describing in a merry mood the winter night when he enjoyed songs and dances performed at Bubyeongnu.

In sum, Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong was an important background for the scenic sights that could be enjoyed around the walled city of Pyeongyang on boat or sleigh. The literati regarded the route from Yeongwangjeong to Bubyeongnu as a significant passageway to enjoy the landscape around Pyeongyang and the Daedonggang River.

An Essential Place to Enjoy Music, Songs, and Banquets

Envoys headed to China constantly had the diplomatic documents they were bringing reviewed through an extra confirmation process called

During the Joseon Dynasty, the office of the governor of Pyeongando Province was located in Pyeongyang, where local goods were abundant. Envoys stopping by during their trip to the northwest enjoyed even more special treatment from the local government offices. If they had the time, the envoys went sightseeing around the region, visiting historical sites such as the grave of Gija 箕子 and the remains of King Dongmyeong of Goguryeo. Of course, Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong were among the top viewing spots to relish in music and banquets.

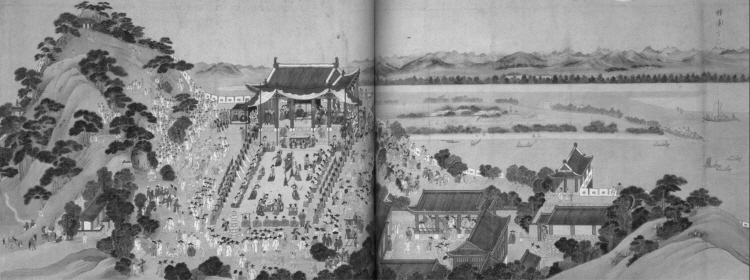

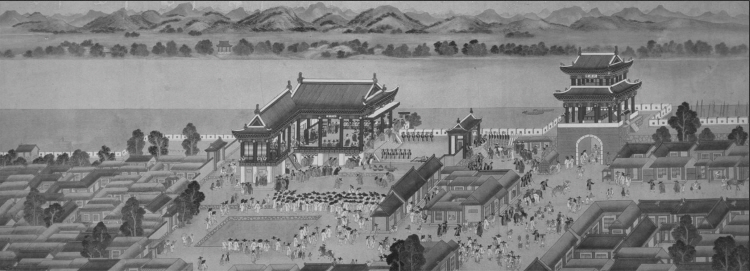

The two paintings

The envoys visiting Pyeongyang on their way to China were highly respected and thus enjoyed the most privileges compared to other visiting literati groups. They would have been treated to a banquet on a similar scale to the welcoming banquet for the governor of Pyeongando, complete with songs, dances, and other forms of musical performances. As long as it was not in the middle of a national mourning period, the province never failed to entertain visitors in either Yeongwangjeong or Bubyeongnu, whether they were high-ranking officials such as the king’s envoys or other literati. The quotations below are records by royal envoys of the banquets and music performances at Yeongwangjeong.

① At Yeongwangjeong, I always feel like the water level is the same as that of the railing of the pavilion. This is because the water’s surface is vast, while the level of the pavilion is just right. I have just found out the reason. Many pavilions are erected close to the river, but it is almost impossible to build them this way. The moon rose not long after that, filling the river with golden waves as the assistant magistrate arranged the musical performance. When they lit the candles inside silk shade lanterns and hung them up on the rafter, the place brightened up like day.24

② I stayed in Pyeongyang. After the envoys gathered at Yeongwangjeong for the confirmation process of the diplomatic documents, a music performance was held.25

③ When the three envoys were done with their document confirmation process, their host prepared a music performance for them at Yeongwangjeong. The railings had open views, so one could look down on the waves and get a full view of the outstanding landscape. The framed board on the front read featured the four-character phrase “Je-il gangsan” (The best of all rivers and mountains 第一江山). There was also a separate verse couplet written on planks on the pillars reading “At one side of a long castle wall, waves run over” 長城一面溶溶水 and “In the east of the wide open field, high-risen mountains appear dotted” 大野東頭點點山. These were written by the Chinese envoy Zhu Zhifan. The poem summed up the overall aspect of the place so well that it became a maxim of the landscape to this day. Among the female entertainers, there were women who could sing the song of a departing ship 離舟曲 and perform the whirlwind dance 旋風舞. People said they were the best out of all the towns along the route of our journey.26

④ In the evening, I paid a visit to the provincial governor, Sim Neung-ak 沈能岳 (1766–?), who also happened to be my distant uncle and then went to the lodgings of the head envoy at Yeongwangjeong with the deputy envoy. There was a huge musical performance that went on well late into the night. Although people say that it is worth taking the time to see the female entertainers of Pyeongyang, those who came to meet me were only country bumpkins. None of the women I once knew were currently active. To me, all the red petals have fallen, and what is left were only green leaves. Though I am perfectly aware that time flies swiftly in the world like a drifting cloud, this seemed all the more so for the female entertainers, and I was not pleased by that at all. Since the girls who took the leading roles in singing and dancing were all born after 1815, they were indeed “planted after Liu Lang” 劉郞去後栽.27 If you dare ask how the banquet was to one truly refined in taste, it would not be all that harsh to point out that one has seen better days with better women.28

Kim Changeop wrote the first quotation above ① on the twelfth day of the eleventh month in 1712, when he was part of a royal envoy group to China together with his older brother Kim Changjip. While gazing at the waves of Daedonggang River swaying under the moonlight, Kim Changeop enjoyed the musical performance at Yeongwangjeong offered by the local government of Pyeongyang. The description of lanterns hanging on the rafters imply that the banquet hall was well equipped with lighting facilities. Seo Yumun composed the second quotation ② on the twenty-eighth day of the tenth month in 1796. After completing the document confirmation process by the royal envoys, a musical performance took place at Yeongwangjeong. Yi Haeeung wrote the third quotation ③ on the first day of the eleventh month in 1803. As did Kim Changeop, Yi Haeeung also mentioned the excellent view observed from Yeongwangjeong. He specifically mentioned how the musical performances offered that night, including the song of a departing ship and the whirlwind dance, made a lasting impression on him. Kim Gyeongseon composed the fourth quotation ④ on the twenty-ninth day of the tenth month in 1832. As his description writes, the music performance at Yeongwangjeong went on late into the night. This was the first time Kim Gyeongseon had visited Pyeongyang in 18 years. His first visit was with his father, who had been appointed as an official in Pyeongyang. In his writing, he compares the musical performance of the past and present. Unlike the others, he evaluates the artistic skills of the female entertainers, pointing out how the current entertainers did not quite measure up to their predecessors in terms of skill.

The quotations above are records of the royal envoys’ experiences in Pyeongyang and were written between late in the tenth lunar month and early in the eleventh lunar month of the year. Since it was already winter, all the banquets and musical performances took place in the hall of Yeongwangjeong. Yeongwangjeong seems to have been chosen for the gathering since it was already serving as accommodation for the envoys and thus saved people the trouble of moving from one building to another in the cold weather. Bubyeongnu’s location, which was relatively far from the inner walls of Pyeongyang, probably made it less ideal for receiving guests to stay the night or preparing a banquet. Most literary works of musical performances or other gatherings at Bubyeongnu consequently were usually reserved for those visiting around spring to autumn, when the weather was milder.

Seong Hyeon 成俔 (1439–1504), a literary figure of the early Joseon period, was appointed to serve in Pyeongyang for a term. He held banquets at Bubyeongnu for the envoys returning from honoring the birthday of the Chinese emperor in China and recounted the event in his poem.

Leaning on the high pavilion, I stared vacantly into the far distance, The oars of the boat move, following the river that flows downwards. What a beautiful night, thanks to the bright moon of the Harvest Moon Festival! It is a wonderous tour accompanying those returning home from a journey of ten thousand miles. As the sound of the iron flute carried by the breeze permeates across the cliff, Women with red makeup hold the candlelight to brighten the shore. With feelings pouring out endlessly through thousands of wine barrels, Those who are joyous continue to be joyous, while those who are sad continue to be sad.29 (Seong Hyeon, “On the Fiftheenth, Envoys who Honored the Emperor’s Birthday Returned From Beijing, so I Greeted Them at Bubyeongnu with Songs and Musical Performances Ready and then Took a Boat and Sailed Down the River Under the Moonlight”)

From Seong Hyeon’s account of receiving the envoys and holding a banquet for them on their way back home from China, it is likely that this took place when he was serving as the governor of Pyeongando Province. Seong Hyeon was appointed as Governor in the second month of 1486 at age forty-eight. Since the poem also mentions the mid-autumn harvest festival, the event most likely occurred on the fifteenth day of the eighth month. He brought female entertainers and musicians to the boat and held a feast at Bubyeongnu, letting the envoys relish the moment of songs, dances, and other refined pleasures. Bubyeongnu played the role of a perfect background for fancy gatherings and enjoyment of music and dance while basking in the bright moonlight of the mid-autumn night.

The banquet at Bubyeongnu also appears in

The weather was clear. I stayed in Pyeongyang. At noon I took a boat and sailed up to Bubyeongnu to watch the sword dance and then moved to the Deugwollu Pavilion at Yeongmyeongsa Temple to take a break. Afterwards, I climbed up Moranbong Peak to look at Eulmildae Pavilion and Gija’s Grave. The sun was down when I returned to my lodging through Janggyeongmun Gate.30

This was recorded on the twenty-second day of the fourth month in 1828. When Yi Jaeheup stayed in Pyeongyang, the weather was warm enough to prepare a feast and musical performances at Bubyeongnu. The sword dance Yi Jaeheup’s traveling party saw had been officially staged at the government banquet in Pyeongando Province during the eighteenth century and spread across the nation. The dance was one of the representative art genres of Pyeongando Province and a must-see performance for envoys dropping by the region on their way home from China. With landscapes such as Moranbong Peak, Daedonggang River, and Neungnado Island playing the background, the performances at Bubyeongnu would have benefited from the additional rich colors of the backstage. Bubyeongnu thus was the perfect stage to hold banquets and musical performances for the enjoyment of the visiting literati.

During the Joseon dynasty, Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong stood as the two representative pavilions in the northwestern region of the Korean Peninsula. They were also known as the birthplace of numerous literary works, inspiring countless literati groups who toured the area. Even today, these two places, which have been designated as national treasures in North Korea, maintain their fame. This article has analyzed the travel records of the Joseon Dynasty and other poems and prose to find out how the two pavilions managed to captivate literary figures over time and examined how these cultural spaces were used. The research provides an explanation of how the two pavilions could remain a background to several literary works for a long time. The article can be summarized as follows.

First, the literati group who left the capital city of Hanyang usually entered the walled city of Pyeongyang by riding on a boat named Seungbyeokjeong at the Daedonggang River. In most cases, the two pavilions were the first two features to came into view at the crossing point of the river, making a lasting impression on newcomers. Visitors could take in an entire picture of the route of the eastern and northeastern sections of the city, stretching from Daedongmun Gate of the inner walls to the Jeongeummun Gate of the northern walls, at this point. Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong would have stood out since they stood high above the city walls from a distance. They would have appeared as the leading sceneries of Pyeongyang and further piqued the interest of the visitors in their upcoming tour.

Second, visitors did not hesitate to make the efforts to reach the high-risen pavilions of Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong in order to take in the beauty of the surrounding landscape. Yeongwangjeong was the perfect place to look down on Deogam Rock, the rising and falling waves of Daedonggang River, the southern view of Neungnado Island, and Simnijangnim Forest. Bubyeongnu allowed open views of the far-reaching landscape including Yeonggwangjeong and Simnijangnim Forest together with nearby sights such as Neungnado Island, Cheongnyubyeok Cliff, and Janggyeongmun Gate. The gaze around also offered scenic sights of Yeongmyeongsa Temple in the vicinity, Moranbong Peak, and Eulmildae Pavilion far away, ultimately presenting an extensive panoramic landscape for all to appreciate.

Third, the 5-

Fourth, Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong were widely used to hold banquets and musical performances for the literati visiting Pyeongyang. The two pavilions sat against the backdrops of the scenic landscape, which was embraced by the long and winding Daedonggang River. Their positions functioned as the backstage to the banquets and performances, further livening up the atmosphere. Such circumstances inspired visitors to write prose and poems about the place.

As this article shows, Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong provided incredible landscapes for the literati of the Joseon Dynasty to gaze upon and enjoy in various ways. As a result, they have been able to keep up their fame as the top scenic pavilions in the nation. Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong functioned as a medium and inspiration for literary figures to continue to share the panoramic views and their artistic experiences through poetry and prose.

Discussions of cultural geography have grown more active recently, as more attention is being given to how geographic factors could inspire literary writings. I hope this research on the spatial use of Bubyeongnu and Yeongwangjeong can further the discussion on the literary contextualization of geographical space and contribute to systemizing the literary-geographical discourse in the area of classical poetry and prose.