The 19th South Korean presidential election was held in the aftermath of the first presidential impeachment in Korean history and the removal from office of the incumbent president, Park Geun-hye. Unlike the 18th presidential election, in which votes were divided between two major parties, five candidates representing different parties received more than 5 percent voter support among ballots cast in the 19th. A major liberal party candidate, Moon Jae-in (Democratic), was elected with 41.1 percent of the vote. His closest opponent, a major conservative party candidate, Hong Joon-pyo (Liberal Korea Party), received only 24 percent of votes cast. Ahn Chel-soo of the People’s Party, Yoo Seung-min of the Bareun Party, and Sim Sang-jung of the Justice Party received 21.4 percent, 6.8 percent, and 6.2 percent, respectively. Given that President Park’s approval rating had remained in single figures since the corruption scandal first broke in October 2016, this landslide conservative defeat was not surprising.

Considering the longstanding dominance of conservative parties in South Korea, the collapse of the main conservative party raises the question of whether the 2017 presidential election will prove to be a watershed moment for the country. Security threats from North Korea, rapid industrialization, and party competition based on regionalism have produced a so-called “uneven playing field” favoring conservative parties in electoral competition. In all five presidential elections held between 1992 and 2012, the major conservative party candidate received the support of at least 30 percent of eligible voters. In the 19th presidential election, however, support for the major conservative party candidate dropped to less than 20 percent among eligible voters for the first time in Korean history. From the standpoint of the 18th election, at least 20 percent of eligible voters withdrew their support for the conservative party.

To understand the nature of this shift in partisan support, we exploit the fact that any particular vote cast by a group of voters consists of a longterm and a short-term component (Campbell 1966). According to Converse (Campbell 1966, 14), the long-term component is “a simple reflection of the distribution of underlying party loyalties,” while the short-term component reflects “peculiarities of that election.” For example, sociodemographic factors such as gender, race, and social class, and political predispositions such as party identification and political ideology, represent long term factors. Candidate traits and issues raised during campaigns, conversely, constitute short-term forces (Lewis-Beck et al. 2008).

Short-term forces that become important at election time tend to produce fluctuations in election outcomes. They “move the turnout by adding stimulation to the underlying level of political interests of the electorate, and they move the partisanship of the vote from a baseline of ‘standing commitments’” (Campbell 1966, 41). On the other hand, long-term factors are generally seen as having a more stabilizing effect on voting patterns (Dalton 2013; Lipset and Rokkan 1967). The impact of social cleavages, however, is also subject to change. A number of studies note that a decline in the impact of social cleavages is associated with unstable voting behaviors at the individual level and instability in electoral outcomes at the aggregate level (Clark and Lipset 1991; Flanagan and Dalton 1984; Franklin et al. 1991).

This paper asks whether the electoral outcome of the 19th presidential election in South Korea signals a critical election that accompanies a “sharp and durable” change in party-voter alignment (Key 1955), or instead represents a short-term backlash against the corruption scandal and the first impeachment in Korean history. In particular, we focus on the impact of social cleavages—prime examples of long-term factors. Since Lipset and Rokkan (1967), scholars have underscored the role of social cleavages in understanding the formation of party systems and the realignment and dealignment of voter-party linkages. Depending on whether the results of the 19th presidential election are associated with a shift in long-term component attachments, the election can be classified as either a deviating or a realigning election.

To analyze the question empirically, we use both aggregate election data and survey data. At the aggregate level, we exploit “normal” or “baseline” votes (Converse 1966) to capture the long-term component in voting behavior for a locale or demographic group apart from the short-term features of a particular election. We focus on the extent to which the election outcomes in the 19th election deviate from the long-term trend. Given that the aggregate level analysis cannot identify the nature of underlying changes, we also analyze individual-level survey data. In particular, we investigate how major social cleavages, evaluations of economic performance, and other issue preferences affected vote switching at the individual level using the 2017 Korean Election Panel Studies data collected by the East Asia Institute.

Three Cleavages in South Korea

Social cleavages are prime examples of long-term factors (Dassonneville 2016); they shape and condition electoral behaviors. The strength (weakness) of a cleavage system in a given country or period of time is often used to explain its electoral stability (instability) (Bartolini and Mair 1990). In their seminal work on cleavage structure and party systems, for example, Lipset and Rokkan (1967) suggest four different sets of cleavages: (1) subject versus dominant culture, (2) churches versus state, (3) primary versus secondary economy, and (4) workers versus employers. The relative salience of each cleavage is unique to the political and historical development of individual countries, establishing the framework in which party systems have developed since the late nineteenth century. Once established and institutionalized in relevant social and political organizations, “cleavages proved durable long after the objective conditions that led to their establishment had passed” (Franklin et al, 1991, 6). Previous studies suggest that three cleavages are particularly relevant in structuring voting behavior in South Korea: region, generation, and class.

Regional bloc voting is one of the most salient features of Korean politics. In pre-democratized Korea, electoral competition was mainly shaped by the democratic-authoritarian cleavage. Yet, this cleavage often manifested in a regional divide; for example, the Northern region versus the Southern region characterized the 5th presidential election, while the 6th is described as Yeongnam region versus Honam region. With the democratic opening of the country, the democratic-authoritarian cleavage lost much of its political meaning, yet regional voting doubled (Lee 2011). In the 1987 presidential election, voters used the birthplaces of the four major candidates to determine their choices and voted for candidates and parties representing the region where they were born, primarily to express solidarity with those of similar backgrounds. Since then, regional divides have been cultivated as politically meaningful collective identities, and regionally based parties have explicitly deployed regionalism as their electoral strategy. In particular, Yeongnam, in the southeastern part of the country, represents a longstanding geographic core for major conservative parties, while Honam in the southwest has been a stronghold for major liberal parties (Horiuchi and Lee 2007; Kwon 2005; Lee and Brunn 1996; Moon 2005). Some scholars have tried to explain the origin and persistence of regionalism with various accounts such as inter-regional prejudice, the inter-regional gap in economic development, or electoral mobilization led by region-based parties (Lee and Lee 2014). While the recent salience of generational and ideological cleavages may indicate a decline in dominance of the regional cleavage, it still has the greatest explanatory power for understanding electoral competition and voting behavior in South Korea.

A generational cleavage became salient from the 16th presidential election in 2002, when young voters supported Roh Moo-hyun, a liberal party candidate, while older voters supported the conservative Lee Hoi-chang. Given that South Korea has experienced rapid social, economic, and political changes in a relatively short period, it is to be expected that voters in different age groups may have different political perspectives. Yet, the generational divide in the 2002 election attracted scholarly attention because it overlapped with the ideological cleavage. At this time, many also started to see the regional cleavage as detrimental to social cohesion and democratic consolidation, despite its persistent impact on voters’ decisions, due to its suppressive effect on ideologyor policy-based competition. In this context, the victory of Roh Moo-hyun, who was elected with strong support from the young, liberal generation across different regions of the country, indicated the weakening of the regional cleavage along with the rise of the ideological cleavage (Kang 2003).

Division along generational and ideological lines reappeared in the 2004 general election (Choi and Cho 2005; Kim et al. 2008), but since then its significance has fluctuated. The generation gap weakened in the 2007 presidential election and the 2008 general election, possibly due to high levels of abstention among young voters. Yet, it became salient again in the 2012 presidential election, when support for the conservative Park Geunhye and the liberal Moon Jae-in was clearly defined along generational lines.

According to Lipset and Rokkan (1967), the class cleavage—along with the three others they noted—affected the formation of party systems in western democracies. While the rise of post-materialism has weakened its impact (Inglehart 1977), the class cleavage remains one of the most important factors in voter political preferences and electoral decisions in western democracies (Evans 2000). Outside of the western democracies, however, its impact is qualified. According to Randall (2001), non-western democracies have tended to go through nation-building, industrialization and political mobilization simultaneously, limiting the extent to which the class cleavage can become politically meaningful.

For this reason, South Korea lacks a clear class cleavage. Its primary indicators—income level, occupation, and education—rarely affect voters’ electoral choices. When these factors do become significant, the pattern tends to be one of low-income voters or blue-collar workers providing greater support to conservative parties, contrary to the pattern in other industrialized democracies (Kang 2003). Some suggest that the class cleavage in South Korea has been eclipsed by security issues such as attitudes toward North Korea or the National Security Law (Kim and Lee 2005). However, political divisions based on income level or social status have become more salient recently, as economic issues such as the Chaebol reform, welfare spending, and economic democracy have gained importance in recent elections (Cho 2008; Jang 2013).

To investigate whether South Korea’s 19th presidential election was accompanied by a shift in these long-term components, we analyze both the aggregate-level election data and the individual-level survey data. Each analysis has advantages and disadvantages in addressing the question. An analysis based on aggregate-level data provides precise estimates of overall turnout and vote outcomes; however, inference using these data can suffer from an ecological fallacy when trying to understand voter behavior. A survey analysis, on the other hand, enables us to compare voter choices at the individual level. Yet, we know that turnout is frequently over-reported in survey data (Burden 2000; Campbell et al. 1960).

In each analysis, we first examine how voters and groups changed their voting patterns from the 18th election to the 19th, based on Darmofal and Nardulli (2010). They suggest that voters reject their habitual voting patterns in order to promote political accountability or to seek nonincremental changes in policy output, using one of three modes: conversion, mobilization, or demobilization. Conversion indicates that voters vote for a party different from the one they voted for previously; mobilization means that previous non-voters are mobilized to vote; and demobilization indicates that previous voters are alienated and abstain from voting at all.

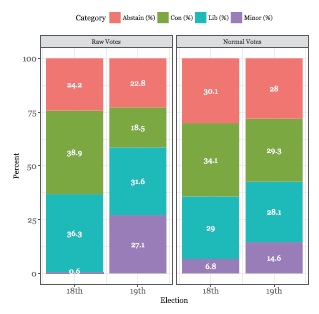

We then proceed to examine whether the inter-election change is accompanied by a shift in the long-term component. Specifically, the aggregate level analysis focuses on the changes in “normal votes.” According to Converse (1966, 11), the actual vote cast by any electorate can be split into “the ‘normal’ or ‘baseline’ vote division to be expected from a group” and “the current deviation from that norm, which occurs as a function of the immediate circumstances of the specific election.” To capture normal votes, we use election return data at the eup-myeon-dong (EMD) level and calculate three election averages: the major conservative party share, the major liberal party share, and the minority candidate share, along with the abstention rate (or turnout).

For the individual level analysis, we examine the panel data collected by the East Asia Institute. The survey has two waves. The first wave was conducted from April 18–20 2017, with a sample size of 1500. The second wave was conducted from May 11–14 2017, with 1157 participants. We focus on changes in electoral choice between the 18th and 19th presidential elections; the question about previous electoral choice in the 18th election was asked during the first wave, and the question regarding electoral choice in the 19th election was asked in the second wave.

Figure 1 depicts how the raw vote variables and the normal vote variables changed between the 18th and 19th elections. In general, the raw vote variables fluctuate to a greater extent than the normal vote variables. In the 19th election, the conservative party share decreased by about 20 percent from the 18th election in terms of raw votes but only by approximately 5 percent in terms of normal votes. The liberal party share decreased by about 5 percent in raw terms, but only by 1 percent in normal terms, while minority candidates’ vote share increased by 26 percent in raw terms but just 8 percent in normal terms. On the other hand, abstention decreased by about 1.4 percent in row terms, but by 1.9 percent in terms of normal votes. The general trend, however, appears similar between raw votes and normal votes. The comparison of electoral outcomes between the two elections suggests that the inter-election difference is comprised primarily of a conversion of majority party supporters to minority candidates, along with a moderate level of mobilization.

To understand the extent to which the election outcomes in the 19th election deviate from the long-term trend, we present Figure 2. Each panel depicts the association between the normal votes and the raw votes at the EMD level for the two major parties in the 18th and the 19th elections. In Panel (A), the X-axis denotes the normal vote share for the conservative party in the 17th election, and the Y-axis denotes its raw vote share in the 18th election. The solid black line denotes the 45-degree line. In the 18th election, the conservative party generally gained additional support beyond its normal vote share in the 17th election. The R2 is from a bivariate regression between the two variables, indicating that 82 percent of the variation in the conservative party share in the 18th election can be explained by the normal conservative party share in the 17th election.

Panel (B) illustrates the association between the normal conservative vote share in the 18th election and the raw conservative vote share in the 19th election. In general, support for the conservative party in the 19th election is weaker than the normal conservative vote share in the 18th election, with the margin increasing slightly in places where the conservative party has strong support previously. However, the R2 indicates that the normal vote share in the 18th election explains 85 percent of the variation in conservative-party support in the 19th election. In other words, the corruption scandal generally reduced support for the conservative party but did not alter the impact of the long-term component in conservative-party support in the 19th election, compared to its support in the 18th.

On the other hand, Panels (C) and (D) suggest that realignment appears to be more salient in liberal-party support than in conservative-party support, if at all. In both elections, the liberal party gained more support than its normal vote share in the EMDs where its normal vote share is low, and less in the EMDs in which its normal vote share is high. In other words, liberal party support differed systematically from its normal vote share in both elections. Moreover, the R2 diminishes from 0.88 in the 18th election to 0.77 in the 19th election, indicating that liberal party support in the 19th election deviated from its long-term trend to a greater extent than it did in the 18th election.

For the individual-level analysis, we first examine changes in electoral choice between the 18th and 19th presidential elections. Again, the question about previous electoral choice in the 18th election was asked in the first wave, and the question about electoral choice in the 19th election during the second wave. Table 1 provides a cross-tabulation of respondents’ choices in each election.

[Table 1.] Cross-Tabulation of Vote Choices in the 18th and 19th Elections

Cross-Tabulation of Vote Choices in the 18th and 19th Elections

The results suggest that the mode of change at the individual level is more nuanced than shown in the aggregate level analysis. First, conversion notably occurs between major party supporters. Among previous Park supporters in the 18th election, 24 percent voted for Moon in the 19th election. Among previous Moon supporters in the 18th election, 1 percent voted for Hong. Second, the majority of minor candidate supporters (54%) in the 18th election also voted for Moon in the 19th election. Third, newly mobilized voters were also divided. Among the respondents who abstained previously, 45 percent voted for Moon, and 29 percent for Ahn. Among previously voting ineligible respondents, 58 percent voted for Moon and 24 percent for Sim.

While these patterns are interesting, the results demonstrate the limitations of probing the extent of conversion and mobilization using the individual-level survey data. First, as noted above (e.g. Burden 2000; Campbell et al. 1960), turnout is commonly over-reported in survey data. Among the 1157 respondents, about 98 percent answered that they voted for a candidate in the 19th presidential election. Only 2 percent chose “don’t know” or are missing from the dataset. Second, the sample overrepresents Moon supporters. In the 18th election, Moon received 48 percent of votes cast and was defeated by Park with 52 percent. In the survey data, however, among the respondents who voted in the 18th election, about 53 percent said they voted for Moon and 41 percent for Park. Survey results for the 19th election suffer from the same problem: 54 percent of survey respondents said that they voted for Moon, while only 15 percent reported voting for Hong. Third, the percentage of voters who abstained in the 18th election was under-represented in the survey data, as, at the aggregate level, 24 percent abstained. Abstentions in the 19th election are similarly underreported, making it impossible to evaluate the relative contribution of the mobilization and demobilization channels to the electoral outcomes.

Despite these limitations, the evidence suggests that the changes between the two elections were driven primarily by vote switching by previous major-party supporters. As evidenced by the relatively high turnout, both elections were held in highly controversial political contexts. Moreover, given that turnout is a strongly habitual behavior, the extent of mobilization and demobilization is likely to be qualified. Meanwhile, only 0.6 percent of voters voted for minor candidates in the 18th election. The share of voters switching from minor candidates to major-party candidates would thus be negligible.

The analysis in the previous section indicates that conversions among previous major-party supporters was the primary change in the 19th election. Is such a shift a kneejerk reaction to the corruption scandal and subsequent impeachment, or might it represent evidence of fundamental changes in voter-party alignments? To answer this question, this section examines who crossed party lines and why. For this analysis, we divided previous Park and Moon supporters in the 18th election into two groups: those who stayed and those who switched in the 19th election. We then examine how demographic characteristics, evaluations of the economy, and issue preferences affect the probability of switching parties.

The list of demographic variables includes sex (0: female, 1: male); age categories (1: 19–29, 2: 30–40, 3: 40–50, 4: 50–60, 5: 60s and up); marital status (0: not married, 1: married); education (1: middle school, 2: high school, 3: university and above); monthly income level (1: under 2 million won, 2: 2–3 million, 3: 3-million, 4: 5–7 million, 5: 7 million and up): region of birth (Sudogwon, Honam, Yeongnam, Other);

We also examined respondents’ ideology (1: liberal, 2: moderate, 3: conservative); evaluations of family and national economy (1: much better, 2: better, 3: same, 4: worse, 5: much worse); attitude regarding impeachment (0: oppose, 1: support); attitude regarding Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) deployment (0: oppose, 1: support); preference regarding North Korea policy (0: engagement, 1: hard line); preference between rooting out corruption or promoting social cohesion (0: rooting out corruption, 1: social integration)

Summary Statistics

In Table 3, we examine four linear probability models to understand how these factors affect major-party supporters’ probability of switching.

[Table 3.] Analysis of Switching Decisions

Analysis of Switching Decisions

Column 1 suggests that regional and generational cleavages have significant effects on previous Park supporters’ decision to switch. In terms of region, the baseline is respondents in the category of Other. The coefficient on Honam is positive and significant, indicating that respondents from Honam are 25 percent more likely to switch than respondents from Other. The coefficient on Sudogwon is insignificant. The coefficient on Yeongnam is negative but significant at the 10 percent level, indicating that respondents from this region are less likely to defect. In terms of age group, the baseline is respondents older than 60. The coefficients for 19–29, 30–39, and 40–49 are significant, but the 50–59 category is not. Thus, respondents younger than 50 are 20–30 percent more likely to switch than respondents older than 60, indicating a clear generational gap in the probability of switching. The coefficient on income is positive and significant at the 10-percent level, suggesting that respondents with higher income are more likely to switch. In contrast, subjective class perception is not significant. Neither sex nor marital status has a significant effect on conservative voters switching. The results in column 1 suggest that three major cleavages in South Korea affected the intra-party split of the conservative party.

To better understand what induces conservative voters to switch, column 2 considers the effects of ideology, economic evaluations, and five policy issues. For ideology, the baseline is conservative. The coefficient on liberals indicates that they are 15 percent more likely to switch to other parties than conservative respondents. There is little significant difference between moderates and conservatives. Evaluation of one’s family financial situation has no significant effect, but those who evaluate the state of the national economy negatively are more likely to switch to other parties. Among the five policy issues, impeachment has a strong effect on party switching: respondents who support impeachment are 40 percent more likely to switch parties than are those who oppose impeachment. Support for engaging with North Korea and increasing welfare also increase the probability of switching by 13 percent and 9 percent, respectively. Note that the influence of the regional and the generational cleavages is still meaningful in column 2, although the magnitude of their impact diminishes.

In column 3, we examine the effect of demographic variables on the probability of switching among previous Moon supporters. Unlike in column 1, the regional cleavage has no significant effect, but the generational difference exists. Those over 60 are more likely to switch than other age groups. Income, subjective class, sex, and marital status have no significant effect. In column 4, only attitudes toward North Korea and rooting out corruption have significant effects on one’s switching decision. Those who support a hardline policy toward North Korea and put more weight on promoting social cohesion over rooting out corruption are likely to switch to other parties. The generational cleavage becomes insignificant; in other words, the difference in column 3 between respondents over 60 and younger respondents seems to be driven by differences in issue preferences. The results in Table 3 show that regional and generational cleavages affect the switching decisions of conservative party supporters.

To further analyze the heterogeneity of conservative party supporters, we also examine their voting decisions using a multinomial logit model.

[Table 4.] Analysis of Alternative Party Choice of Park Supporters

Analysis of Alternative Party Choice of Park Supporters

Column 1 compares support for two major-party candidates. The results show that ideology, evaluation of the national economy, impeachment, and policy toward North Korea affect respondents’ choice of Moon over Hong. Liberal and moderate voters are more likely to vote for Moon than Hong. A negative evaluation of the national economy and support for the policy of engagement with North Korea also increase the probability of voting for Moon. Controlling for ideology, economic performance, and other policy issues, neither the regional cleavage nor the generation gap has a significant effect. Column 2 compares support for Hong and Ahn. In contrast to column 1, columns 2 and 3 suggest that there is no significant difference in issue preferences between supporters of Hong, Ahn, and Yoo, aside from the impeachment issue. The coefficients on Honam and the age groups indicate that Ahn received greater support among respondents from Honam and from voters younger than 60. Similarly, Yoo received greater support from respondents whose ideology is liberal and from voters in their 30s.

The results in Table 4 highlight interesting heterogeneity among conservative party switchers. Supporters of Ahn and Yoo differ from Hong voters only in their support for impeachment among policy issues. Given that the significance of the impeachment issue will wane over time, this division will become less salient, opening up the possibility of rejoining. In contrast, the differences between switchers to Moon and other voters seem more conspicuous. Are they going to continue to support Moon once the impeachment issue has lost its salience, or will they return to the conservative party?

With this in mind, we compare the issue preferences of three groups: core liberal party supporters, conservative swing voters, and core conservative party supporters. Core liberal (conservative) party supporters denote respondents who voted for the liberal (conservative) party in both elections. Conservative swing voters are those who voted for Park in the 18th election but for Moon in the 19th election. In Table 5, ideology shows the average value of ideology in each group. Other cells show the proportion of respondents who support each issue. It is clear that swing voters and core liberals commonly support impeachment. Swing voters are also closer to core liberals than core conservatives in average ideology scores, attitudes toward North Korea, and attitudes toward growth. On the other hand, swing voters seem closer to core conservatives on THAAD and promotion of social cohesion. The results suggest that impeachment drives the coalition between swing voters and core liberals. Thus, while swing voters lean toward core liberals in their ideology score, it is not clear whether this coalition would be sustainable. As their attitudes toward North Korea and THAAD suggest, swing voters have ambivalent preferences. They prefer engagement with North Korea to hardline policy, but they also prefer the promotion of national security manifested by the deployment of THAAD. Whether swing voters will maintain their current coalition with core liberals or rejoin core conservatives in times of aggravated security threats remains an open question.

[Table 5.] Comparison of Policy Preference

Comparison of Policy Preference

This paper examines how the corruption scandal and subsequent impeachment affected voter decisions in South Korea’s 19th presidential election. Both the aggregate and individual-level analyses demonstrate that primary changes from the 18th election were due to vote switching by major-party supporters. The aggregate-level analysis suggests that at least 25 percent of eligible voters voted for a different party in the 19th election, the majority of them having previously been Park supporters. Assuming that the extent of mobilization and demobilization was limited, about 20 percent of eligible voters defected from the conservative party. Considering the longstanding dominance of conservative parties in South Korea, the collapse of the main conservative party raises the question of whether the election qualifies as a “critical election” coined by Key(1955, 17), in which “there occurs a sharp and durable electoral realignment between parties.” At this moment, it is difficult to tell whether this change will be durable. Instead, we question whether the election accompanies fundamental changes in the long-term component of voter-party alignments based on social cleavages in South Korea.

Our analysis suggests that the abrupt splintering of the main conservative party is likely to represent an instantaneous backlash against impeachment rather than a harbinger of voter realignment in South Korea. At the aggregate level, the impact of normal votes on conservative party support in the 19th election does not decline compared to the 18th election. At the individual level, the regional, generational, and class cleavages in South Korea are still influential in voters’ switching decisions, particularly among conservative voters. Among previous Park supporters, respondents who are younger than 50 or from Honam were likely to switch to other parties even after controlling for various individual-level covariates. Liberal ideology, a negative evaluation of the national economy, support for impeachment, support for engagement with North Korea, and support for welfare policy are also positively associated with a decision to switch.

A further analysis also reveals that conservative party switchers are not homogeneous. Aside from support for the impeachment of Park, voters who switched to Yoo and Ahn hold similar attitudes to those who remained with the conservative party. Once the political salience of the impeachment issue wanes, Yoo and Ahn supporters are more likely to return to the conservative party than to remain with the liberal party. On the other hand, it is difficult to foresee the future party preferences of switchers to Moon. Like core liberal voters, they support engagement with North Korea; but, like core conservative voters, they support the deployment of THAAD. Such ambivalence suggests the possibility that they may withdraw their support for Moon in times of heightened security threats.