This article explores the intersection of state-sponsored policies of anticommunism and discourses surrounding sex in 1970s South Korean popular culture through an investigation of bangong seongin manhwa (anti-communist adult comic books). The following analysis examines the merging of sex and anti-communism in these cultural texts and considers how they were consumed and interpreted by readers during the Yushin period. Following the promulgation of the Yushin Constitution in October 1972, anti-communist slogans and messages featured more prominently in public life and stories of espionage and counter-espionage were popularized to support counter-intelligence policies. South Korean President Park Chung-hee stressed chongnyeok anbo (all-out national security) and argued for the strengthening of anti-communist education. These domestic initiatives corresponded to a changing international situation. Following the declaration of the Nixon Doctrine in 1969, a spirit of international reconciliation emerged and during the decade of the 1970s a shift toward a post-Cold War order began. During this decade, economic development in North and South Korea allowed both countries to attain an outward appearance of modernity. Subsequently, the two countries entered a period of competition between their opposing political systems, while domestically leaders of both countries sought to fortify rule over their domestic populations. Animated by the zeitgeist of international rapprochement, the two countries signed the July 4th North-South Korea Joint statement in 1972. However, conversation between the two countries languished before collapsing altogether. Meanwhile, both countries utilized popular media to reinforce political ideologies and fortify authoritarian power while also criticizing the opposing side’s political system. Amidst Dictator Park Chunghee’s campaign to indefinitely extend his rule, films, television shows, and popular music were deployed to emphasize anti-communist slogans. In addition to attacking the Park Chung-hee administration’s anti-communist ideological message as deceptive and false, North Korean propaganda in the form of books and leaflets denounced corruption in South Korea and declared North Korea’s system to be morally superior.1

In the following sections, I examine the popular consumption of anticommunist adult comic books as a unique sub-culture existing in 1970s South Korea which arose out of the confluence of anti-communist discourse and an explosion of sexualized content in entertainment media at a time when political power deeply intervened in all aspects of popular culture. Specifically, this article examines the interplay between anti-communism— the cornerstone of the Yushin regime—and “obscene” sexuality—an ostensible object of eradication by the regime. The article also considers the types of audiences reading anti-communist adult comic books and the ultimate cultural implications of these trends (Maeil Business Newspaper, October 2, 1971; Dong-A Ilbo, December 20, 1971).2

In contrast to the atmosphere of strict suppression of “obscene” expressions of sexuality during the Yushin regime in South Korea, sexual content increasingly appeared in popular films and magazines. The weekly tabloid Seondei Seoul (Sunday Seoul) gained popularity for its risqué articles, and films featuring young women working at hostess clubs, such as Byeoldeul-ui gohyang (Heavenly Homecoming to Stars, 1974) and Yeongjaui jeonseong sidae (Yeong-ja’s Haydays, 1975) proved popular with cinema audiences. Amidst an atmosphere of increasing public visibility of sexual themes, tabloids like Seondei Seoul testified to the public’s appetite for erotic material (Kwon et al. 2015, 252–253). Indeed, in the early years of its publication, the tabloid’s front pages featured salacious gossip columns and erotic articles (Im and Park 2013, 109), a development indicative of the public’s mass consumption of women’s bodies in popular culture (Park 2010, 165). Correspondingly, hostess melodramas featuring young female protagonists who move from the countryside to Seoul only to end up working at bars and nightclubs emerged as the representative genre of 1970s South Korean film.

Adult comic books enjoyed even greater popularity and precipitated the growth of sexual themes in popular culture.3 Adult comic books appearing after the Korean War were advertised as “adult fiction” and distributed mainly on newsstands and at manhwabang (comic book rental shops). Representative comic book series such as Go U-yeong’s Im Kkeokjeong (1972), and Kang Cheol-su’s Sarang-ui nakseo (Scribbles of Love, 1974) gained popularity as comics containing explicit representations of sex. Most adult comic books relied on violence and strong imagery to attract readers’ attention. However, although hostess films provided voyeuristic pleasure for audiences, these films avoided controversy regarding their sexual content by purporting to display the anguish caused by industrial modernization through the character of an impoverished lower-working class woman. In addition to persistent plagiarism controversies, adult comic books were commonly stigmatized as cheap and obscene. Adult comic books were referred to as bullyang manhwa (junk comics) and eumnan manhwa (lewd comics). Indeed, anti-communist adult comic books that began appearing in 1974 were a product of both the state’s adoption of anti-communism as an official state policy and increasingly audacious representations of sex in popular culture.4

Multiple Korean studies scholars have discussed anti-communist cultural texts produced during the Park Chung-hee regime. South Korean scholar Yu (2007, 39–40; 59) discusses how the commercialization of sex and violence was combined with anti-communism in television dramas to spotlight the bellicosity and cruelty of North Korean Communists.5 Jun (2014, 164–181) analyzed the 1970s South Korean film series Teukbyeol susa bonbu (Special Investigation Bureau, 1973–1975) to unpack the interrelation between the body of the female spy depicted on the screen and anti-communist ideology. Other studies have focused on anti-communist animations such as the Ttori janggun series (General Ttori, 1978–1979) (Oh 2015, 452–474; Yun 2014, 162–177). Additional research by Han (2009, 101–109) has categorized the anti-communist and anti-North Korean content of comics serialized in newspapers into four distinct types. However, no significant research has been conducted on anti-communist adult comic books openly distributed at manhwabang and newsstands. An exception is Kim (2015, 187–189) personal recollections on the “boom of anticommunist adult comic books” that became popular beginning in the early 1970s.

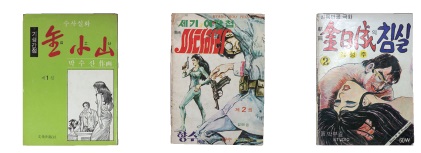

This article adds to previous research by analyzing the foregrounding of male sexual fantasies in adult comic books that purported to dramatize the realities of communism in the service of anti-communism and antiespionage campaigns. Table 1 presents the titles of all extant anti-communist adult comic books from this era. The majority of the comics are mystery stories that revolve around a female spy. In the process of narrating stories of male heroes exposing and eliminating female enemy spies, the female spy’s sexuality is repeatedly exhibited and exploited beyond the needs of the narrative. This article examines three comic books from 1970s: Segiui yeogancheop Mata Hari by author Hyangsu (Mata Hari: Female Spy of the Century, 1974–1976), Gisaeng gancheop Kim So-san by Park Su-san (Gisaeng Spy Kim So-san, 1975),6 and Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil by Park Bugil (Kim Il-sung’s Bedroom, 1974–1976). All three comic books enjoyed sustained popularity among audiences and uniquely highlight the common characteristics of anti-communist cultural texts.7 Indeed, a common trait of anti-communist adult comic books is their claim to be based on true stories and their propensity to transform salacious rumors into quasi-pornographic dramatizations—all genre conventions present in these three comic books. In addition, whereas Segi-ui yeogancheop Mata Hari and Gisaeng gancheop Kim So-san can be compared to other films and radio programs, the content of Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil appears in no other media form, making the analysis of this comic book even more valuable.

Newsstands and manhwabang grew rapidly in 1970s South Korea and served as the main venue for the distribution of adult comic books. In post-1960s, children and adolescents emerged as the primary consumers of comic books and manhwabang served as the exclusive space where young people could spend leisure time (Son 1998, 173–174).8 Indeed, adults were not the sole consumers of adult comic books. Adolescents easily accessed comic books at places such as barber shops and schools. Newspaper articles frequently warned against the spread of vulgar and lewd comics and their harmful effects on children (Kyunghyang Shinmun, June 14, 1974). Unsurprisingly, adult comic books also made their way into the hands of young children, and the reading of adult comic books by youth was regarded as a social ill (Figure. 1). As South Korean cultural critic Kim (2015, 187) recalled, “The overwhelming majority of readers of adult comic books were middle and high school students curious about sex”.

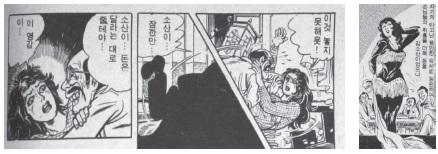

Anti-communism also functioned to shield adult comic books from government censorship and regulation. Adult comics often elicited controversy for being more vulgar and pornographic than movies and television dramas of the time. The comic Segi-ui yeogancheop Mata Hari was criticized for “containing ridiculous and vulgar scenes and being a lewd comic containing explicit dialogue”—however, the comic continued to be serialized. Likewise, the comic Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil also continued to be serialized despite being more graphic than previous adult comic books (Chosun llbo, December 6, 1974). During this time, publishing companies’ registrations were revoked due to controversies over the harmful effects of adult comics on children. Additionally, a system of pre-censorship for comic book publication was put in place. Still, anti-communist adult comic books managed to avoid censorship and were openly distributed despite containing sexually explicit content.

For example, in response to controversy concerning vulgarity and obscenity in the comics of Park (1974), the author excused his behavior by stating, “In my efforts to openly expose the inhuman and unethical aspects of Kim Il-sung, I unintentionally violated the ethical standards of publishers” (1974, 2:2). Authors commonly used the prefaces of their comic books to evoke the threat of enemy spies and reaffirm the peril that accompanied the advance of communism. On the book covers and in the prefaces of all three comic books discussed here, the authors warned readers of the danger presented by espionage, and they justified their works under the pretext of exposing the hideous nature of Kim Il-sung. However, the comic books had the opposite effect, as the intense and alluring images of naked female bodies overwhelmed the anti-communist premise.

Together with anti-communism, historical accuracy served as the grounds by which authors justified explicit depictions of sex. After the television series Silhwa geukjang (True Life Drama) was broadcast on KBS in 1964 for the purposes of arousing anti-communist sentiment, anticommunist narratives in radio dramas, films, television shows, and novels began to appear more frequently—such as the film series Teukbyeol susa bonbu (Special Investigation Bureau) and the television drama 19-ho geomsasil (Prosecutor’s Office No. 19) broadcast on KBS. Whereas some publishers lost their registration to publish adult comic books as a result of strengthened censorship of obscene printed media, anti-communist adult comic books effectively avoided censorship by claiming their intentions to express thoroughly anti-communist ideology through the dramatization of historically accurate stories.

Oh Je-do, a real-life anti-communist prosecutor, appeared as a leading character in both films and comic books that claimed to be based on true stories, and he personally wrote a preface to the comic book Gisaeng gancheop Kim So-san attesting to the story’s authenticity (Jun 2017, 55–56). Cartoonist Park (1974a, 2:50), who authored Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil, emphasized that his work was “created based on actual past events and historical evidence, as well as the testimonies researchers and witnesses.” Hyangsu (1974, 1:3), the author of Segi-ui yeogancheop Mata Hari, explained that “although I took some artistic license in its creation, the events concerning Mata Hari herself are as true as possible.”

Emphasizing historical accuracy in the telling of anti-communist narratives was a means to justify excessively sexual themes in a variety of texts. Indeed, films and comic books that claimed to be based on true stories routinely featured sexuality erotic female enemy spies and rumors about the bedroom affairs of Kim Il-sung, “the notorious fraud and sex maniac.”

In 1970’s South Korea, stories about female spies were spread not only through books and films, but also in the gossip columns of the tabloid Seondei Seoul. After the formation of the South Korean government, rightist magazines such as Bukan teukbo (North Korea Newsbreak) and Ibuk tongsin (North Korea Report) began to report on Kim Il-sung’s womanizing (Bukan teukbo, December 1949; Ibuk tongsin, April 1950). Sensational reporting also covered female spy Kim Su-im’s execution just before the outbreak of the Korean War (Dong-A Ilbo, June 14, 1950; Kyunghyang Shinmun, June 17–18, 1950), and rumors about Kim So-san, a gisaeng (female entertainer) who worked at Gugilgwan (Gugil Hall) were also written about in newspapers.

Although films and comic books about female spies reproduced similar subject matter and plot lines, they differed in the way they embodied sex and targeted reading audiences. The six films in the Teukbyeol susa bonbu film series held varying ratings; one film was targeted at elementary school students, while other films were targeted at high-school students and adults. However, anti-communist adult comic books were classified as exclusively adult-only material, and renting or selling them to minors was clearly marked as prohibited. Consequently, while the showing of sexual activity in movies was relatively restricted, comic books demonstrated an unlimited imagination concerning the sexual escapades of female spies and the sex life of Kim Il-sung.

The following chapter explores the representation of female spies as illustrated in Gisaeng gancheop Kim So-san and Segi-ui yeogancheop Mata Hari. The article then turns to analyze the representation of the North Korean dictator Kim Il-Sung in Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil. My analysis focuses on the comic book’s ability to elicit empathy from readers by portraying frightening female spies as sources of amusement, and constructing Kim Il-Sung—the ultimate enemy that must be toppled—as a masculine phallic symbol. These comic books transform arousing rumors into visual images that satisfied the voyeuristic desires of readers. Repositioning communism, traditionally a source of fear and terror, as a source of pleasure to deliberately attract male readers was a strategy particular to the production of anticommunist adult comic books. More specifically, this article examines how the exhibition of female sexuality and the pornographic elements of anticommunist adult comics were at odds with the comic books’ expressed anti-communist intentions, which functioned as a political justification exempting adult comics books from government censorship.

Authors of anti-communist adult comics exploited anti-communist themes in order to distribute their comics free from censorship, contributing to the appropriation of sensational sexual content for commercial gain in popular culture. For example, cartoonist Park Su-san switched from producing romance comics to anti-communist titles such as Gisaeng gancheop Kim So-san and 19-ho geomsasil precisely at a time when the government was encouraging the production of anti-communist materials and creative content combining anti-communist ideology and sex was becoming popular.

During World War II, stories of spies were intentionally spread to secure internal control over war-time Korea (Kwon 2005, 178). Spy narratives appeared again in the post-liberation period amongst rising Cold War tensions and took on new nationalistic meanings within the context of a divided Korea. In the process of Korea being re-born as a nation-state after liberation from Japanese rule, interest in and rumors about the real-life female spies Bae Jeong-ja and Kim Su-im multiplied. The biography of Kim Su-im, who was an active member of the Worker’s Party of South Korea, frequently appeared in newspapers. Dong-A Broadcasting aired the popular radio drama series Teukbyeol susa bonbu for 10 years starting in 1970, and episodes about female spies such as Kim Su-im and Kim So-san were made into a total of five films.

Discourses concerning female spies and espionage were resurrected on screen and in broadcasting during the Park Chung-hee regime, and the creators of such stories commonly highlighted female spies’ bodies and life stories. Unlike the representation of powerful and competent female spies that were a product of the racist discourse underlying the logic of Japanese colonial rule, female spies depicted in 1970s Korean films were notably portrayed as erotic yet passive, overly melodramatic characters (Jun 2014, 169-170). For instance, the first film in the series, Teukbyeol susa bonbu: gisaeng Kim So-san (Special Investigation Bureau: Gisaeng Kim So-San, 1973), begins by explaining that Kim So-san became a spy for love and ends with the scene of her execution. As director Seol Tae-ho noted, the film was basically a melodrama “that focused more on the woman’s tragic life trapped between love and ideology than on her espionage” (Dong-A Ilbo, January 26, 1973). Moreover, the film was rated as appropriate for adolescent viewers and was limited in its explicit dealings with sexual themes.

By contrast, although adult comics borrowed from the same rumors and stories, they purposefully emphasized the sexuality of female spies to appeal to male readers. The spies featured in adult comic books were Mata Hari, an exotic figure unfamiliar to Korean readers, and Kim So-san, an already famous subject of gossip.

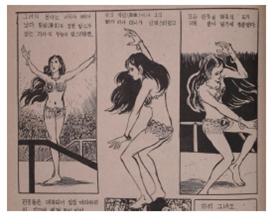

Segi-ui yeogancheop Mata Hari by author Hyangsu was popular enough to be published in 14 volumes over three years from 1974 to 1976. The preface claimed that the series “expressed the story as closest to the truth as possible,” and the comic book illustrated Mata Hari’s life from birth until death. The author depicted her as a femme fatale who developed her dancing to appease European tastes and used her body to obtain honor and wealth. The author also disclosed his intention to reveal the spy’s muchgossiped about bedroom during the process of telling the story of Mata Hari’s life.

The author defined Mata Hari as a “nude dancer, a subject of lewd scandals, and a mysterious and fantastic sex queen of the orient,” thereby stimulating readers’ orientalist imaginations. Just like the western men within the narrative who visited theaters and bars to witness Mata Hari’s body and dancing, South Korean readers also approached the comic books as a medium to witness the spy’s body. In response to readers’ expectations, the author gradually reveals the spy’s sexual adventures of dating men for material gain and eventually engaging in espionage. Mata Hari begins her career as a spy after receiving payment for hiding a German spy, and she later participates in German intelligence operations to gain greater material rewards.

The narration in Segi-ui yeogancheop Mata Hari doubly objectifies Mata Hari, “who has oriental blood,” by describing how she learned about the goddess Siva’s dance, revealing a sexual imagination inflected by racism. To illustrate “a house of prostitution in Paris” and “a bedroom in the court,” the author inserts scenes of nude dancing and sex—scenes which could not have appeared in Korean films of the time. In short, provocative and orientalist images of the dancer Mata Hari were ultimately visualized through the medium of comic books. Although this work did not contain egregiously obscene drawings, the author sexually objectifies Mata Hari by eroticizing her body parts and inserting rape scenes depicting men desiring the femme fatale, a spy supposedly “more horrifying than a hydrogen bomb.”

Although the narrative begins by describing how Mata Hari exploits her body to succeed as a spy, by the end, the narrative transitions to a court room drama where an older Mata Hari express her regrets. Films and radio dramas of the time deployed a similar narrative grammar which placed sexually alluring female spies at the center of the narrative, only to transform them into sources of amusement and objects of sympathy by the conclusion of the story, neutralizing them as potential threats.

Author Hyangsu stated that he dramatized the story of Mata Hari because he wanted to heighten the public’s awareness of communism. Commenting on his intention for the comic book, he mentions past events such as the Kim Su-im spy incident and provocations by Kim Il-sung’s cabal, and states that the story of Mata Hari—the “quintessential spy”—could inspire South Koreans to stay vigilant against the “followers” of Mata Hari hiding in South Korean society.

However, the author’s motivations go beyond contributing to the government’s anti-espionage campaign. Hyangsu deliberately foregrounds the erotic dances and sexual escapades of Mata Hari. Indeed, his work allowed readers to consume female spy characters as sexual objects. Erotic images of Mata Hari covered the pages of the comic book, and the narrative’s self-proclaimed significance as an anti-communist cautionary tale and historical dramatization was rendered meaningless in the process.

To understand Gisaeng gancheop Kim So-san, another comic book depicting a female spy, it is necessary to compare it with the film Teukbyeol susa bonbu: gisaeng Kim So-san directed by Seol Tae-ho, which dramatized identical subject matter based on the testimony of prosecutor Oh Je-do. The film is the first of the Teukbyeol susa bonbu series and it places the female spy Kim So-san, whose life has been ruined in the pursuit of love, at the center of the narrative. It is notable that Oh Je-do, the spy-hunting persecutor, is not the main protagonist. The film and comic book were based on the same radio drama script, and therefore the plot developments are nearly identical. In addition, Oh Je-do himself reviewed the historical facts presented in the works. However, it is worth noting that the comic book places less emphasis on the unfortunate life of Kim So-san, instead focusing on the fall of Gugilgwan, a high-class restaurant, and the activities of Oh Je-do. Moreover, it depicts Kim So-san not as a character worthy of empathy, but rather as an object of voyeuristic pleasure. The 1970s in South Korea were characterized by an explosion in sexual discourse, and adult comic books were likely more successful than movies at exhibiting the female body.

The film adaptation of Kim So-san’s story utilized melodrama to appeal to female audiences and achieve popular success. Actress Yun Jeong-hui played the part of Kim So-san in the film despite not holding sex-symbol status with the public, a directorial choice not repeated in subsequent installations of the series. Instead, Yun Jeong-hui portrayed a character who expresses regret regarding the unfortunate decisions she made because of love. Beginning with her career as a spy and ending with her execution, the film concentrates more on Kim So-san’s regrets than on the exploits of the special investigation bureau.

Contrastingly, the comic book adopts a male point of view that scrutinizes every movement of Kim So-san’s body. The female spy exists only as an object of voyeuristic pleasure, and the emotions of love and betrayal are invested with little importance. In the comic book series, Kim So-san is blinded by material greed and affection for her lover, Im Chungsik. Consequently, she contacts an organizer of the Worker’s Party of South Korea and begins actively participating in espionage operations by exploiting her sexually appealing body. In the film, actress Yun Jeong-hui dances with her clothes on, whereas the comic book depicts a slightly more explicit and sensual dance scene. Moreover, close-up shots in the film show the regretful face of Kim So-san with a cigarette dangling from her lips. The comic book frequently shows Kim So-san as a naked hula dancer.

The comic book Segi-ui yeogancheop Mata Hari shows the female spy’s nude dance staged in theaters. Similarly, Gisaeng gancheop Kim Sosan depicts Kim So-san’s strip show in Gugilgwan. Furthermore, Mata Hari was referred to as a “sex queen,” and Kim So-san was similarly called the “queen of the red-light district” and “queen of the night.” Sexual encounters in the comic books are often scenes of prostitution and rape, and the two female spies are represented as objects of male violence and amusement. The only difference is that in Gisaeng gancheop Kim So-san, the female spy is simultaneously an object of voyeurism and a pupil of the anti-communist hero, prosecutor Oh Je-do.

Although author Park Su-san devotes considerable space in the comic to showing the debauched parties taking place at the high-class restaurant Gugilgwan, he also deliberately positions the characters from the special investigation bureau’s office as existing at the opposite end of the ethical spectrum. Park Su-san subsequently attempts to gratify publishers’ expectation for anti-communist and counter-espionage plot lines by describing Oh Je-do as an anti-communist hero “indifferent to drinking and womanizing.” However, similar to how the tale of Kim So-san’s tragic life eclipses and renders insignificant the investigator’s dedication to anticommunism in the film, the comic book focuses on stimulating readers’ base desires at the expense of developing Oh Je-do’s character.

By constructing female spies as sexually alluring characters, these comic books sacrificed both historical accuracy and the ability to deliver effective anti-communist messages. Both Gisaeng gancheop Kim So-san and Segiui yeogancheop Mata Hari attest to the level of debauchery and eroticism anticipated by male audiences consisting largely of teenagers. The former comic book took the form of an epic narrative of the life of Mata Hari, and the latter contained relatively fewer lewd images as it focused on the investigation by Oh Je-do. However, both works professed a commitment to an anti-communist agenda while garnering popularity by stimulating male readers’ imaginations concerning female spies. Indeed, adolescents enjoyed these comics as adult themed entertainment rather than anticommunist propaganda (Kim 2015, 187–189). Anti-communist adult comic books featuring stories about enemy spies existed at the intersection of three converging interests: publishers who wanted to follow government policies while pursing commercial aims9; writers who wanted to attain mass appeal; and readers who sought out pornographic content. In the process, the effectiveness of anti-communist messages was severely compromised. If that is the case, how was Kim Il-Sung—a common object of media sensationalism— represented in South Korea comic books after the division of the Peninsula?

The comic book Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil authored by Park Bu-gil dramatizes rumors about the North Korean dictator Kim Il-sung, which circulated in South Korea after the establishment of the government in 1948. Previously described as the “tiger of Mt. Baekdu,” Kim Il-sung began to be portrayed as a “bad boy” and “sex maniac” in monthly magazines such as Ibuk tongsin and Bukan teukbo after a number of leftist activists defected to North Korea, and South Korea increasingly turned to the right. Likewise, flyers and books published in North Korea elaborated on rumors about Park Chung-hee’s penchant for sensual pleasures (Kim 1978, 63–66). Indeed, the North and South Korean medias reported on rumors concerning the sexual depravity of the opposing country’s leader as fact as a means to attack the legitimacy of their opponent’s political system.

After Korea was liberated from Japanese rule, curiosity concerning personal stories of Kim Il-sung grew in South Korea. Images of Kim Il-sung were constructed out of the personal stories of those who visited North Korea during the liberation period and the testimonies of North Korean intellectuals who defected to South Korea. Before the establishment of separate governments in the North and South, Han Il-u reported on Kim Il-sung’s activities in the independence movement based on an interview he conducted with him. Han contended that a man known as Kim Seongju, an independence fighter known as Kim Il-sung, and the current General Kim Il-sung in question were all the same person, refuting rumors of a fake Kim Il-sung that were based on the ruling of the Pyongyang Courthouse (Minseong, January 20, 1946). Han Seol-ya, a writer who had defected to North Korea, similarly described General Kim Il-sung as “a man with the common touch and a devotion to his work” (Minseong, February 1, 1947).

After the foundation of the South Korean government, an entirely different image of Kim Il-sung based on eyewitness accounts began to circulate. Oh Yeong-jin, an intellectual who defected to South Korea, first suggested the theory of a fake Kim Il-sung in his book Sogunjeonghaui bukan: tto hana-ui jeungeon (Oh, 1952), which was published after his defection in 1947. His self-proclaimed “testimony” played a significant role in the process by which rumors became recognized as historical facts (Yi 2016, 230–231). Kim Ryeol also appealed to eye witness accounts to argue that the patriot Kim Il-sung had already died, and that the current Kim Il-sung was an imposter. He added that Kim Il-sung had plundered and massacred fellow countrymen in Manchuria and killed his wife Kim Jeongsuk (R. Kim 1949, 16–17).

Voices that praised Kim Il-sung as a tiger of Baekdusan (Baekdu Mountain) or maligned him as a sex maniac and thug both argued the veracity of their stories by claiming their assertions were based on eye witness accounts. However, such accounts were in truth based on personal experiences and organized to a certain extent to satisfy the curiosity of the South Korean public. Nevertheless, rumors about Kim Il-sung were consistently represented as fact and incorporated into anti-communist accounts. An article released during the Korean War about Kim Il-sung’s extravagant vacation home satiated the public’s curiosity (Chosun Ilbo, October 25, 1951; March 2, 1953) and after the war rumors about Kim took the form of memoirs that presented themselves as fact.10

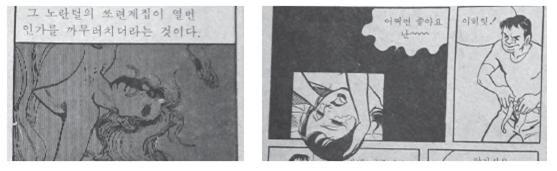

Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil dramatized rumors concerning Kim Il-Sung and denigrated him as a sex maniac and murderer, all the while defending the story’s veracity. The author chronologically recounts the life of “the killer monster Kim Il-sung,” and revisits major historical events such as the Bocheonbo jeontu (Battle of Bocheonbo, 1937) and the Sinuiju haksaeng uigeo (Sinuiju Student Protest, 1945). In the process, he re-circulates various rumors from the liberation period as historical fact, such as those about a fake Kim Il-sung and the murder of Kim Jeong-suk. Moreover, Park Bu-gil deliberately selected stories of violence, murder, and the promiscuous sex, as such content could be easily exploited by the comic book medium.

Despite claims of historical accuracy, comic books were little more than lewd stories depicting the most lascivious rumors of Kim Il-sung arranged in chronological order. Around the time of the Yushin regime, the Munhwagongbobu (the Ministry of Culture and Public Information) expressed its intention to strengthen pre-censorship of comic books that significantly influenced national ethics and teenage sentiment. Regarding adult comic books, the ministry clearly stated that the “description and expression of excessively lascivious or obscene content” was prohibited, and the Hanguk doseo japji yulli wiwonhoe (Korean Ethics Commission for Books and Magazines) launched aggressive crackdowns (Dong-A Ilbo, June 12, 1975). Regardless, Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil was widely distributed and escaped censorship on account of its professed anti-communist intentions, despite being considerably more pornographic than other adult comics.

Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil began publication in 1974, and new installments were at first released two weeks apart.11 The speed of publication was possible largely because the book’s motif was based on rumors already well known to the public, and the author’s imagination was required only to insert scenes of sex and violence. The exact number of units in circulation is unknown, but considering that that two different series of Kim Il-sungui chimsil were published at the same time due to a conflict regarding publication rights, it can be assumed that the series enjoyed considerable popularity.12

The narrative focuses on a brutal gang led by Kim Il-sung and the ordinary people they exploit, particularly women. The comic book shows only victims of Kim Il-sung without presenting any male heroes such as the anti-communist prosecutor Oh Je-do. The comic book begins with Kim Ilsung’s childhood and shows him possessing an exaggerated sexual curiosity similar to his father. The narrative then portrays the series of events by which Kim Il-sung becomes ruler of North Korea. Volume 1 describes the life of young neighborhood thug Kim Seong-ju (Kim Il-sung’s real name) and Volume 2 covers the process of Kim Il-sung being chased by Japanese police and raping Kim Jeong-suk, who lived in the same neighborhood, before he runs away to Manchuria. In Volume 3, he changes his name from Kim Seong-ju to Kim Il-sung and impersonates an independence fighter, after which he returns to his hometown and takes Kim Jeong-suk as his woman. Volumes 4 and 5 explain how Kim Il-sung took hold of political power in North Korea after fabricating his past and relying on powerful Soviet men. Finally, in Volume 6, Kim Il-sung rapes Choi Seung-hui, a dancer who defected to North Korea, and consequently faces death threats from infuriated patriotic young Korean men in Sinuiju.

Every volume of Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil concludes with Kim facing extreme danger. For instance, in the last scene of Volume 2, Kim Il-sung is about to be killed by the head of a group of Manchurian bandits after Kim rapes the man’s wife. Volume 3 ends as Kim Il-sung is about to be shot by Kim Jeong-suk’s husband as revenge for raping his wife. The author ends each volume with the same question, “What will happen to Kim Il-sung?” Because Kim Il-sung was alive in the present day, readers knew he could not die. These cliffhangers created no actual suspense and these comic books attracted readers solely through audacious illustrations of sex and violence.

Moreover, these sex scenes were inspired by rape fantasies. Both Segiui yeogancheop Mata Hari and Gisaeng gancheop Kim So-san repeatedly show female spies engaged in prostitution and facing the risk of being raped. However, Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil goes one step further. Female characters appear during scenes of rape, only to again vanish. Female characters in the book appear and disappear solely for their function in Kim Il-sung’s rape scenes. Most sex scenes in the comic book portray Kim Il-sung raping innocent women. Before leaving for Manchuria, Kim Il-sung breaks into the house of Kim Jeong-suk, who had rebuffed his advances in the past, and rapes her. After joining a group of bandits in Manchuria, Kim Il-sung rapes the innocent wife of the bandit chief. In short, this comic book is rape pornography starring Kim Il-sung.

Suspense is created in the stories by following Kim Il-sung’s multiple and changing strategies for raping women. At first he fails, but he eventually gets what he desires. Indeed, the suspense is raised in the story when Kim Ilsung evades the attention of the drunken bandit chief and rapes his virgin wife in the next room. The author uses explicit language, stating that Kim Ilsung “rode” the woman. In response to controversy concerning the obscene aspects of the comic, the publisher explained that Volume 3 would contain less lewdness and instead concentrate on Kim Il-sung’s dissident purges and family disputes. However, the subsequent volumes continued to show Kim Il-sung’s ceaseless attempts to rape and assault women.

Kim Il-sung stands out as a unique character in the genre of anti-communist adult comic books. The characters of Mata Hari and Kim So-san became spies as a consequence of other primary motivations such as extravagant taste and love. Additionally, these characters are placed in romantic love stories which appealed to the sympathies of readers. On the other hand, Kim Il-sung was presented as a murderous demon and an enemy of the nation. He deserved to be purged, just as the author described. Nevertheless, apart from the thoroughly anti-communist ideology, comic book readers tended to identify with Kim Il-sung in his conquest of women’s bodies in the rape scenes of the comic book. That is, readers observed women’s bodies vicariously through Kim Il-sung’s eyes. Readers eager to consume pornographic narratives likely hoped for Kim Il-Sung to survive until the next volume so he could continue with his bizarre sex endeavors. In short, as the main protagonist of pornographic narratives, Kim Il-sung became an object of identification for readers. The ultimate enemy in these comics, Kim Il-sung, is a character that cannot die, the ultimate irony of anti-communist adult comics.

Published after heated controversy over its pornographic aspects, Volume 3 of Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil begins showing Kim Il-sung raping and looting Korean expatriates in Manchuria, and then suddenly jumps forward in time to describe a conflict between Kim Il-sung and his grownup son, Kim Jong-il. This appeared to reflect the author’s promise to portray Kim’s family disputes in more detail after his book was criticized for its pornographic nature. Kim Jong-il also appeared as a character in Kim Ilsung- ui chimsil: nat-gwa bam, an unofficial volume that resulted from a disagreement over publication rights.

In the unofficial comic, Kim Jong-il leaves for the Soviet Union as a young man to study. The author describes him as a man with an impressive sexual prowess who captivated Russian women and enjoyed a promiscuous sex life. Considering that the unofficial volume emulated the original book’s subject matter and world view to confuse readers of the time, it is worth noting that both the original volumes and the unofficial volume released by the publisher both inserted factors to make readers yearn for the father and the son.

In addition, despite the author’s promise to moderate sexual content, Volume 3 presented even more extreme content. Gongbi (Communist guerillas) plunder Korean expatriates and gangrape civilian women. Moreover, while describing how Kim Il-sung took power in North Korea and raped the famous dancer Choi Seung-hui, the book inserts the dancer’s real photograph on the pretext of assisting readers’ understanding. Furthermore, the book contains a scene in which North Korean politician Choi Hyeon travels with Kim Il-sung to Choi Seung-hui’s house and subsequently rapes her 16-year-old daughter.

In the book, Kim Il-sung was not just a thug, a poor family man, and the subject of terror and sympathy—he was also the object of envy for readers who indulged in the comic book’s rape fantasies. Moreover, Kim Il-sung and his son possessed impressive sexual prowess and likely became the objects of both envy and sympathy for adolescent and adult male readers alike.

Due to the lack of primary sources, it is impossible to confirm exactly how long Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil was published. Kim’s pornographic adventure may have continued for many years, but it is also possible that the book’s publication was halted due to the recurrent controversies over obscenity. However, considering that the time period described in Volume 6 was still shortly after Korea’s liberation, it is possible the series’ storyline continued into the 1970s, the time period during which the comic books were published. Indeed, because Kim Il-sung was alive at the time of the series publication, he could not die in a comic book that claimed to be historically accurate. In other words, unlike Segi-ui yeogancheop Mata Hari or Gisaeng gancheop Kim So-san, it was impossible to conclude Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil with a didactic ending. Indeed, there was no way of ending the story at all. In the process of revealing Kim Il-sung’s vices, the author indulged in presenting increasingly extreme sexual descriptions.

Anti-communist adult comic books were a unique product of the time. Neither the authors nor readers invested meaning in the anti-communist themes. Instead, both the authors and consumers prioritized sex over anticommunist ideology in the creation and consumption of texts. Comic books served as a medium capable of exhibiting explicit images unavailable to films and were accessible to younger readers through newsstands and manhwabang. Park (1976, 3:2) admitted that his work “ran counter to the code of ethics for publishers” and asked for understanding, yet continued creating obscene comics. As Kim Chang-nam stated in his memoirs, it is notable that “what was important was anything but the story.” He labeled Kim Il-sung-ui chimsil a “lewd comic book wrapped in anti-communist ideology.” He further explained that what was most important to teenage students, the main readers of adult comics, was “showing naked women’s bodies, regardless of whether the main character was Kim Il-sung or not,” and that anti-communism was only the “vehicle and pretext” for readers to enjoy sex (Kim 2015, 187–189).

Because anti-communist adult comic books of the 1970s claimed to target adults while exploiting commercialized images of sex and violence, they were able to employ a narrative grammar different from movies and radio dramas. Radio dramas about female spies utilized sound effects to heighten listeners’ sense of suspense. Movies borrowed the narrative techniques of melodrama to dramatize the tragic and tumultuous lives of female spies. In contrast, anti-communist adult comic books chiefly targeted adolescent and adult males, offering them glimpses of female spies and Kim Il-sung’s bedroom.

In 1980, immediately following the end of Park Chung-hee’s administration, the Ministry of Culture and Public Information announced a plan to eradicate lewd comic books that stimulated young readers’ criminal psychology. In this process, Hyangsu and Park Su-san, the authors of Segiui yeogancheop Mata Hari and Gisaeng gancheop Kim So-san, respectively, were arrested for their use of obscene and violent imagery. Later, obscenity became the domain of pornographic films, one of the nationally encouraged areas under the infamous “Three S Policy,” which encouraged sex, sports, and (movie) screens. Anti-communist adult comic books, therefore, constituted a unique reading culture in 1970s South Korea.

As this article demonstrates, the mass consumption of anti-communist adult comic books in 1970s South Korea was intertwined with the phenomenon of a rapidly expanding public discourse on sex. Compared to other entertainment media, adult comic books of the 1970s were more explicit in their depictions of sex and violence and were likewise criticized as vulgar and cheap. However, anti-communist adult comics were able to evade censorship and openly create pornographic content under the guise of anti-communism. To satiate a politically repressed public’s appetite for explicit content, authors delivered audiences comic books portraying Kim Il-sung’s sadistic sexual exploits and female spies’ naked bodies under the pretense of exposing the evils of communism. In describing the life of the North Korean dictator and the tragic lives of female enemy spies, anti-communist adult comic books relied heavily on the exploitation of women, and readers were encouraged to enjoy women’s bodies without selfreflection. Consequently, under the pretext of dramatizing the real-life ills of communism, these comic books avoided censorship and were distributed to young male readers, resulting in a unique reading culture. In the process, powerful images of naked female bodies overwhelmed the presence of anticommunist messages and brought about the opposite effect of the comics’ professed anti-communist agenda.

Anti-communist adult comic books aligned themselves with the vulgar desires of male consumers in 1970s South Korea, revealing the authors’ and publishers’ obvious commercial incentives behind their choice of subject matter. Important to note is that communism was correlated with obscenity and pornography, locating both outside of acceptable social norms. Simultaneously, although female spies and Kim Il-sung functioned as symbols of communism, within these texts they materialized not as objects of terror or hostility but of pleasure and amusement. In this respect, readers could enjoy the explicit displays of sexuality present in anti-communist comic books without hesitation. In the comic books discussed here, communism was brought into the realm of everyday life and readers gazed at women’s bodies depicted in the books through the eyes of the dictator Kim Il-sung.

In the process of consuming salacious material present on the pages of comic books, female spies and rape victims became objects of amusement while Kim Il-sung and his son became objects of identification and envy for readers. In fact, readers had to root for Kim Il-sung as the protagonist in order for the series to continue. Therefore, the anti-communist messages contained in anti-communist adult comic books were subverted. Reading for pleasure consciously and unconsciously exposed the limitations of the political ideology of the Yushin regime. Certainly, the reading culture of anticommunist adult comic books indulged male readers’ voyeuristic desires and was both sadistic and perverted. However, around the time when the Yushin regime was introduced, sexual imagery and themes exploded within popular culture while authorities championed ethical stoicism founded on anti-communism. Against this backdrop, such perverse and contorted narratives emerged and could be distributed publicly.

This essay examined anti-communist adult comics as a form of popular culture which emerged in the 1970s among intensifying competition between the North and South Korean political systems. The content of anti-communist adult comic books demonstrates an aspect of 1970s South Korean popular culture that grew freakishly out of an inflexible political atmosphere. These cultural texts also reveal the possibility for popular culture to be produced and consumed in ways at odds with the desires of authorities. Considering these facts, the distribution of anti-communist adult comic books in 1970s South Korea is noteworthy in that it produced a reading culture which clearly revealed the hollowness of anti-communist slogans while also subverting authorities’ policies of cultural regulation.