In postwar South Korea, many women worked as insurance agents, including working-class women, middle-class housewives, war widows, and single mothers.1 That employment was critical, since many were the breadwinners in their families. Other than registering with the Ministry of Finance, no other special qualifications or advanced degrees were required, making these jobs accessible to women at a time when few employment opportunities were open to them. Until the late 1960s, however, men made up 70–80 percent of agents.2 That situation reversed in the 1970s: more than 80 percent of agents were women and 70 percent were widows,3 who flocked to that industry in search of much-needed income. By 1988, women dominated the industry: 93.6 percent of life insurance agents were women.4

The dramatic increase in the number of female agents was due to both the appeal of flexible employment for women with family responsibilities and the rapid growth of the personal insurance market. Female agents were typically assigned to that sector, which involved sales to individuals, families, and small businesses. They worked extremely hard, employing persistence, skill, sincerity, and social capital, notably their ability to build trusting relationships with customers, which resulted in spectacular sales figures that spurred the rapid growth of South Korea’s insurance industry.

Social capital, a fundamental part of community-based mutual aid organizations since premodern times, also played a crucial role in South Korea’s burgeoning insurance industry from the 1960s to the 1980s. Korean terms commonly associated with social capital, yeongo and yeonjul, refer to social ties based on hyeoryeon (kinship), hagyeon (school), or jiyeon (a shared locality such as people from the same hometown), which reinforces the idea of a collective “us” at the heart of those relationships. Many Koreans believed that insurance subscriptions, notably gwonyu gaip and yeongo gaip, partly succeeded because clients felt compelled to purchase a policy to avoid shaming the agent and jeopardizing their relationship. Yet, little research exists on female insurance agents and solicitation subscriptions except a few studies that rely on surveys and statistics from the 2000s (Lee et al. 2010). Most scholarship examines South Korea’s insurance industry from sociological or business perspectives—for instance, the role of insurance agents (Yi and Jeong 2001), the legal status of insurance jobs (Kim 2015), and the competence of insurance agents and their relationship with customers viewed through a business model lens (I. Park 2016), with a paucity of research on female agents despite their dominant role in the industry.

This paper attempts to develop research on South Korea’s insurance industry from the 1960s through the 1980s by focusing primarily on life insurance, and to determine why solicitation sales—gwonyu gaip (solicitation subscription)5 and yeongo gaip (subscription through social capital) in particular—became so popular.6 We can ask whether that relationship between agent and customer was a new type of social bond that augmented well-established types of social cohesion that already formed the bedrock of Korean interpersonal interactions. Also, should solicitation subscription sales be seen solely as part of a trust-based reciprocal relationship? Deeply entrenched gender bias in the insurance industry, as elsewhere in South Korea during the postwar economic development period, and the devaluing of women’s expertise and achievements stem from a long-standing cultural bias that assumes men and male professionalism should dominate the workplace. Yet, the total volume of individual insurance sales already outpaced that of corporate/group sales in the 1970s, which indicates that solicitation sales dominated the market. This paper argues that female agent solicitation sales of insurance made historical ruptures in the long-existing male-dominated social network in businesses in South Korea. Female agents’ success in solicitation sales transformed the insurance industry’s profit structure from corporate/group clients to individual ones. This accompanied more women’s entry into the financial market but simultaneously manifested in the feminization of insurance sales.

Modern insurance was formed to resolve psychological insecurity or the feeling of “crisis” arising from the fear that a state’s welfare system cannot completely protect against a personal emergency (Ericson et al., 2003, 10–11). This characteristic suits the development of the insurance industry in South Korea, where postwar public instability for the future and a passion to overcome poverty fueled its growth. For instance, so-called “education insurance” to prepare for children’s education expenses perfectly met many parents’ enthusiasm for their children’s upward class mobility.

Another Korean specificity is that conglomerates’ dominance in the industry further solidified family owners’ management and expansion of their businesses. Some large companies’ insurance affiliations could provide capital for conglomerates’ other affiliations through loans, which, in turn, intensified market share and oligopoly. Samsung’s Dongbang saengmyeong (Dongbang Life Insurance) is a case in point. Yi Byeong-cheol, Samsung’s founder, took over Dongbang in 1963, the year after Dongbang’s foundation. Dongbang immediately became the number one life insurance company in terms of performance, but also the second largest shareholder in Samsung. The insurer focused on investing in Samsung’s affiliations, such as loaning ₩700 million to Samsung’s Hanguk biryo (Korean Fertilizer), investing ₩193 million in Daehan jeyu (Daehan Oil), and investing ₩400 million in Sinsegye Department Store. Dongbang was called “a safe for Samsung chaebol.”7 Other major conglomerates similarly adopted this method.8 Most conglomerates’ family owners devised identical tactics to maintain their corporate governance by elevating insurance companies as their major shareholders, internally providing capital for affiliations with liability problems. The top three life insurance companies took 75 percent of the entire reserves, and the gap between leading and small-sized insurers widened.9

Also, the Park Chung-hee regime’s economic plans required additional domestic savings sources along with bank savings. The global economic downturn triggered by two oil shocks and decreasing national savings led the Park regime to mobilize more domestic savings. Instead of establishing a fundamental welfare system, Park urged insurance companies to take more “responsibility to mobilize domestic capital”10 to cash in insurance reserves to implement the ongoing national economic development plans. Park’s strategies to grow the second financial institutions (je-2 geumyunggwon) left adverse precedents, as South Korean financial laws banned direct bank ownership by conglomerates but not by secondary financial institutions, such as securities or insurance firms and money lenders. Ironically, this led to conglomerate practices of cross-shareholding (Chang 2003), lax management, and expansion of their businesses. The power of conglomerates did not directly affect the growth of solicitation sales, but these political-economic specificities can better our understanding of the historical context around emerging women-led individual sales in South Korea’s insurance industry.

The South Korean insurance industry’s rapid growth and major conglomerates’ market dominance do not necessarily mean that social networks automatically worked as a panacea for insurance sales. During the Park regime, social campaigns and government movements promoting frugality and economic moderation through saving ironically hindered recognition of the benefits of insurance’s risk coverage. Client tendencies to use an insurance policy as another form of savings were reflected in the preference of insurance policies. Household savings-type insurance with a guaranteed principal (gagye jeochukseong boheom) accounted for 86 percent of life insurance subscriptions in Korea in 1979.11 Unlike Daehan Education Insurance’s popularity, life insurance needed agents’ marketing efforts to convince clients of the need for these policies. Female life insurance agents relied on social capital to develop effective relationships with their prospective clients based on mutual trust as a way to boost solicitation sales to individual customers and small businesses. Jaeyeol Yee (2000) divides social networks into those with weak or strong social ties and explains that members of the working class and older Koreans tend to have stronger and more emotional relationships, partly in response to South Korean authoritarian regimes from the 1960s to 1980s.

Another scholarly discussion surrounds the question of whether social capital can create economic capital. Among others, Robert Putnam claims that network capitalism, or social capital, played a significant role in the rapid economic growth witnessed in South Korea and other parts of East Asia from the 1960s through the 1980s. He notes that vibrant informal financial networks that facilitated saving and investment existed among East Asian women, both in their home countries and in the diaspora, as exemplified in Amy Tan’s spirited 1989 novel, The Joy Luck Club. In that novel, Chinese immigrant women gather in San Francisco to play mahjong and engage in financial activities, but it is their personal relationships, forged over time, that bind them together in that club and make it work, demonstrating that “social capital can be transmuted, so to speak, into financial capital” (Putnam 1993, 5). Yet, his claims receive criticism that social capital is not always fairly transformed into economic capital for the benefits of community members (DeFilippis 2001).

Similarly, social network transformed into economic capital in South Korea from the 1960s to the 1980s when married women eagerly participated in gye, a type of microfinance rooted in late Joseon-era peasant life that was then modernized into rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs). The economic success of gye relied as much on the close social relationships between women as on their financial acumen, since housewives collaborated financially with one another (E. Park 2018). Group cohesion characterized gye, whereas selling solicitation subscriptions depended on individual relationships between insurance agents and clients.

Why then were solicitation sales so pervasive, particularly in insurance subscriptions in the 1970s? Because insurance sales rely so much on trust, social capital, and avoiding shame, they are far more complicated than the sale of most other commodities. When social capital is an integral part of the transaction, expectations are different. For instance, from the 1960s onwards in South Korea, direct or door-to-door sales of books, cosmetics, small electronic devices, and home appliances increased substantially.12 The fact that these consumer goods were considered necessities drove sales, rather than any social connection between consumers and sellers. The immediate utility and desirability of those consumer goods were obvious to consumers and fueled purchases. By contrast, the appeal of an insurance policy, especially life insurance, lies in its long-term value; it is viewed as an investment for the future, not merely the present. A female insurance agent had to skillfully employ her social capital to cultivate a trust-based relationship with each client and success was never guaranteed. Not every client purchased a policy and some cancelled their policies because they were dissatisfied either with the service or the terms of the contract, or both. These post-subscription conflicts suggest that solicitation subscriptions did not always generate the mutual benefits that social capital should facilitate.

Life insurance’s selling point of future preparation certainly attracted new subscriptions of individual insurance policies, but although large conglomerates were already familiar with problematic business customs from past experience, illegitimate practices like rebates and credit contracts continued because clients were aware of such business customs and expected to take advantage of them, and insurers could not stop because of fierce competition. Further, male agents could commit infractions with impunity, and even be rewarded for those misdeeds, while female agents, despite their success in sales that fueled the spectacular growth in personal insurance, were unjustly accused of unprofessionalism. Compared to personal insurance subscriptions, group/corporate subscriptions were valuable, as were the associated commissions, which could be as large as 15 won on every 1000 won.13 Not only did male agents sell most group/corporate insurance subscriptions, they were also more likely to be involved in group insurance malpractice like giving out rebates. Rebates and other dubious methods of gaining and keeping clients were cunningly developed in the 1960s and continued for decades, deepening the collusion between insurers and corporate clients. For example, insurers gave corporate clients conditional contracts with the understanding that they would also loan them funds to pay their premiums. That way, new clients found it very easy to afford a subscription through rebates and loans.14 In contrast, insurance companies did not establish an overall system to support personal insurance sales. As the following sections will outline, wage policies that determine base pay and incentives especially did not properly reflect female agents’ performance. Gender hierarchies were maintained, as was the feminization of insurance in the 1970s and 1980s. Had South Korean conglomerates’ life insurance companies continually made a majority of their profits in group/corporate insurance subscriptions, the insurance industry might have become another typical example of a male-centered industry. Corrupt practices involving male agents and their corporate clients were widespread but usually occurred in private, while the pressure tactics used by female agents to boost personal insurance sales were readily apparent to ordinary citizens and the media and, therefore, subject to intense public scrutiny and criticism. Thus, the success or failure of selling solicitation subscriptions depended not just on an agent’s social capital but also on a more complicated interplay between client and agent, economic factors, and systemic issues within the insurance industry.

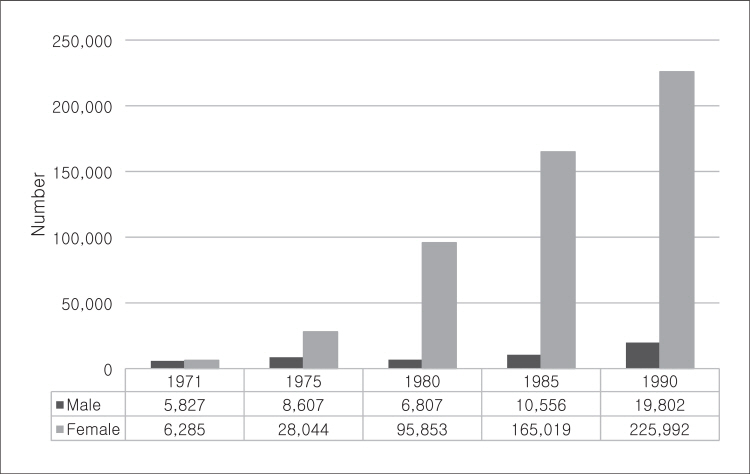

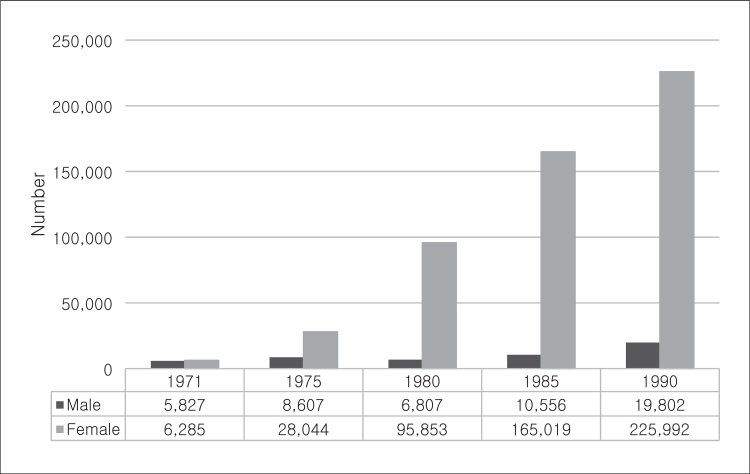

This paper mainly uses the primary sources of the financial newspaper Maeil gyeongje sinmun (Maeil Business Newspaper), the industry magazine Saenghyeop (Life Insurance), and women’s magazines to analyze several noticeable phenomena within the insurance industry. This paper also references comprehensive statistics compiled by the Korea Life Insurance Association (KLIA), although many aspects of this data do not correspond with news reports. Considering the Maeil gyeongje sinmun is a well-known financial newspaper and news reports showed consistency among themselves, both the news outlets and the KLIA must have employed their own legitimate methods to obtain their data, otherwise all would be incorrect. Finally, this paper uses selected news articles that clearly convey pertinent data related to specific topics with consistent tones and figures over the two decades that are the focus of this research. Because the relevant calculation formulas for figures are not clarified, this paper primarily refers to news articles, with the exception of the two categories below provide simple figures such as the number and gender of insurance agents (Table 1) and the number and monetary value or amount of new subscriptions (Table 2).

While the gender ratio of agents and the growing gap between them in Table 1 concurs with news reports, the sum of fees of new group insurance subscriptions as given in the KLIA data is far lower than individual ones throughout the 1970s. The gaps between these KLIA figures and the insurance situation as described in contemporaneous news reports in the 1970s and 1980s are significant.

The number of new group subscriptions in Table 2 remains mostly higher than that of individual ones, but the total amount of fees for group subscriptions remains consistently lower than for individual subscriptions throughout the two decades covered by the data. In 1979, for instance, the number of new group subscriptions is nearly two times higher than that of individual ones, but the total amount of fees is nearly half than that of individual ones. Overall inaccuracies in the data may relate to the industry’s complicated calculation methods to yield values and implies that improper business practices, such as rebates and credit loans, could have obscured the results. These incongruous sources are a salient feature of research on the South Korean insurance industry. Because the South Korean insurance industry in the 1970s is an understudied area, there is much room for misconceptions and ambiguities in our understanding of it.

In the 1960s, South Korean insurance companies, particularly the life insurance sector, preferentially hired married women to work in personal insurance to sell policies to individual customers and small businesses. The large number of female agents, coupled with their successful sales records, resulted in the “feminization of insurance sales.”15 This concept of the “feminization of labor” refers to the discrimination against women in capitalist industries that ghettoize female laborers in lower-paid, less-skilled jobs relative to their male counterparts (Caraway 2007, 11). Similar biases existed in the South Korean insurance industry. Even though the phenomenal sales figures achieved by female agents were the result not only of their social capital and skill but also their physical, affective, and intellectual labor, that labor was devalued as expendable. Female agents under intense pressure risked depleting their social capital; ultimately it became so overstretched that it declined and then sales dropped dramatically, policy cancellations rose sharply, and agents resigned in droves. Such problems did not deter other women from seeking insurance agent jobs, so the insurance industry simply hired new agents. Despite rapid turnover, women still dominated solicitation sales to individuals, families, and small businesses, continuing the feminization of insurance sales.

Employment opportunities for women—especially those with diminished social status—increased, but the general public, unaware of the due switch of gender ratios, perceived the job as yet another sex-segregated occupation. Social ignorance of women’s economic activities was nothing new. The consistent contempt for fortune women (bokbuin)16 in postwar Korean society can be likened to the unfair perception of female agents as overbearing and unprofessional, which undercut their credibility, compromised their sales performance, and put their jobs at risk. Nevertheless, South Korean industrialization processes actually helped females to enter the financial sector in roles beyond traditionally female-dominated ones of light and service industries. Top female graduates from commercial high schools were hired as bank tellers, one of the few socially respectable occupations for women along with that of schoolteacher.17 Despite social reputation and decent salaries, bank tellers were mostly younger, unmarried women, whereas insurance agent work was open to married women.18

The feminization of insurance sales reflects the increasing number of women working in that industry from the 1960s through the 1980s, when the number of women selling individual policies far outstripped that of men.19 Working-class women and housewives comprised the bulk of insurance agents because those positions did not require any previous experience or a college degree. Major newspapers ran monthly ads for temporary insurance work targeted at women, such as “30 dollars per month, no higher education degree needed, no previous experience required” in general job posting sections next to postings for construction workers, seamstresses, and housekeepers.20 By contrast, ads for office employees, better and higher-paid work, were posted separately by insurance companies that were looking for “a man with a college degree who had completed military service.”21 These job postings bifurcated along gender lines, that only well-educated men would be considered for managerial positions while women would be relegated to low-level temporary positions. Attracting new clients took time, so female agents were dependent on their base pay until they could build up a large-enough clientele to generate sufficient sales and commissions; this took even more time and effort for agents (mostly female) pursuing individual clients over corporate clients. That put female agents at a further disadvantage since their base pay was much lower than that of male agents.

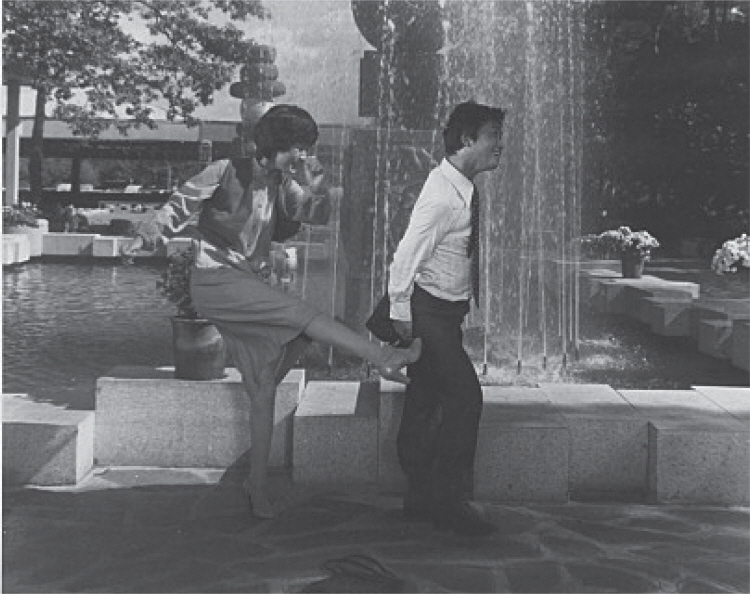

Besides these gendered hierarchies in the wage system, sexual harassment, even sexual assault, of female insurance agents by male customers was an all-too-frequent occurrence that the industry wanted to keep hidden. Considering the appearance of both female insurance agents and instances of sexual violence against them in news reports, film, and television dramas were quite rare, the exposé in the 1979 film Sunakjil yeosa (A Daughter-in-law’s Stubbornness, dir. Kim Su-hyeong) was groundbreaking. The female protagonist, Min Gong-hui, receives accolades from her peers for setting a new subscription sales record, but that rosy outlook suddenly turns ugly when she is threatened with sexual assault. At a male client’s request, Min agrees to meet him in a nearby park. She soon realizes he intends to sexually assault her, so in self-defense she swiftly kicks him (Fig. 1),22 knocks him over, swears at him, and then departs.23

However, having portrayed Min as an intelligent, strong, and confident woman who bravely fends off her would-be attacker—she literally kicks him and, by extension, symbolically kicks patriarchy—the film abandons that liberated view of womanhood and reverts to prescriptive notions of womanly behavior. The personal capabilities that might have facilitated her work performance did not work to change social perceptions of female agents but to associate tenacity with them. Min quits her job, forsaking her highly successful career as an insurance agent, to focus on her primary role, giving birth to a son who will carry on the Chang family lineage.

All these gender-biased impediments frustrated female agents, causing many to resign within the first year of employment. By the early 1970s, the resignation rate for female agents was alarmingly high: nearly 70 percent of new agents left within the first year.24 That figure rose to 80 percent in the 1980s.25 As new subscription rates increased from 29.6 percent in 1976 to 41 percent in 1982,26 cancellation rates also rose sharply—up to 50 percent for life insurance policies in 1977, though this number dropped to 30 percent by 1982.27 Such high cancellation rates were partly due to the rapid turnover in female agents, which caused clients to feel abandoned and view agents negatively. That further eroded agents’ social capital, which precipitated more policy cancellations and agent resignations: a vicious cycle. No matter how many female agents quit, there was an almost unlimited supply of applicants to refill those positions since so few jobs were available to married women. This rapid turnover of agents grew even worse in the 1990s, accelerating the somopumhwa (disposability) of female agents.28 That situation illustrates yet another adverse aspect of the feminization of labor.

High turnover and cancellation rates reflected systemic problems within the insurance industry. Many policy clauses, or even whole contracts, were not translated into Korean. Indemnity insurance firms, for example, offered 279 different contracts written in English but only 169 written in Korean.29 Abstruse language within policy contracts kept both clients and agents from fully comprehending terms and conditions. Pressure to sell policies tempted agents to forego explaining contract details properly to their clients in order to expedite the process. If agents finalized deals too quickly, clients might not be made aware of important factors when making their decision. Such rush jobs tarnished the reputation and social capital of female agents.

Problems within the insurance industry cannot be attributed solely to management’s negligence or an insatiable desire for higher profits. The legacy of colonialism also played a significant role. During the colonial period, Japanese companies had cornered the insurance market both in Japan and on the peninsula, but upon liberation those companies pulled out of Korea, abandoning their customers and refusing to reimburse them for cancelled policies. As a result, those customers experienced huge financial losses, eroding their trust in insurance companies.30 Another remnant was that most of the abstruse language in insurance clauses dated to colonial-era content written by Japanese authorities. South Korean insurance companies had attempted to reform that confusing language but were stymied by American occupation forces.31 The United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) audited insurance payment rates and benefits. In April 1947, USAMGIK decided to enforce Japanese insurance laws. The South Korean government countered that interference by enacting a new insurance law in January 1949, but it differed little from colonial era statutes and a golden opportunity to reform the insurance industry was missed.32

Besides terms and conditions and obtuse language derived from colonial-era insurance contracts, the lack of specialized training and certificate programs for agents coupled with low wages created problems, especially for women working in the life insurance industry.33 Training was alarmingly brief: after a three-day course and just two months of apprenticeship with a senior colleague, a new agent could begin his or her own sales. Wages for South Korean agents were equally bad: life insurance agents, for example, received a base pay equivalent to 25 dollars per month until 1976, when it rose to 43 dollars, but only for agents who had worked for a company for more than a year.34 Indemnity insurance companies were even worse; they refused to provide any base pay to agents until 1984.35 Since the base pay rate was so low, or even nonexistent, agents relied on commissions derived from new sales; the more they procured, the higher their commission. But only 1.7 percent of the first premium paid by a new customer formed an agent’s commission, so it was very difficult for junior agents to earn sufficient income.36 Unable to attract enough female agents in the 1970s, insurance companies were forced to make concessions: they increased commissions on new contracts and created additional financial incentives for agents with good performance records. Also, 2.5 percent of the total insurance payment was now given to each agent under new terms, called useon sudang (priority incentive).37 These improvements aside, commission rates for female agents remained inadequate,38 as did base pay rates, which discouraged agents. Many resigned, but some agents persevered to garner new clients and enhance their commissions. Female agents collected premiums during monthly visits to individual clients—jipgeumje (visits to collect fees)—which provided a constant source of revenue for insurance companies and regular contact with clients could lead to other sales. Clients appreciated these regular visits, which fostered mutual trust and made clients feel respected and cared for by their agents (Kwon 1984, 41). By facilitating jipgeumje as an effective long-term client management technique, female agents expanded social capitalistic features into individual insurance businesses.

Insurance companies constantly tried to maximize profits by increasing fees, reducing payroll costs, and engaging in abusive practices. Agents received 3–4 percent of fees they collected from their clients,39 a relatively small commission that kept payroll costs down. In 1981, electronic billing was adopted, which enabled clients to pay fees at banks,40 but those who liked the convenience of jipgeumje continued to pay their fees during monthly visits from their agents.41 As competition among branch offices intensified, some offices created fake agents and subscription documents so that they would receive additional commissions from headquarters. Other branch offices set ever-higher monthly sales goals and delayed payment of wages to agents who failed to fulfill those goals, even forcing them to pay clients’ unpaid premiums. Due to these abusive practices, the base pay, which was reported to be equivalent to around ₩40,000, was actually under ₩98,000.42 Some clients felt “abandoned or indifferent after signing policy contracts” (Kwon 1984, 40) if they thought agents were not sincere or diligent enough in their customer service; to placate those clients, agents spent excessive time and effort during their monthly visits, which effectively reduced their wages.

Insurance companies recognized that pressure tactics in sales backfired and tarnished the reputations of their female agents, so they tried to “purify” (jeonghwa) that sullied image by sponsoring essay contests among agents. In those essays, female agents were expected to extol the successes they had with insurance sales, their ability to work well with other agents and contractors, and their willingness to help customers with family financial management (Saenghyeop 1984a). Such essays were ludicrous PR trickery, doing nothing to mitigate the underlying problems.

Saenghyeop also had essays that were highly critical of the pressure tactics that typified solicitation sales. Some female agents resorted to begging, even cajoling, clients to purchase policies rather than making sure agents responded properly to their clients’ needs and concerns. The novelist Yi Ho-cheol wrote in the 1978 issue that female agents had to resort to “half begging” to increase sales, and attributed widespread abuse in the insurance sector to the state failing to provide for Koreans with an adequate welfare system, so they had no recourse but to rely on a corrupt insurance industry. Yi lamented that “this relates to the fundamental problems of our society. All insurance, including life insurance, will have to pass social muster since it is our only social security system” (H. Yi 1978, 26).

Like many in South Korea, Yi viewed aggressive solicitation sales as a nefarious marketing practice that harmed clients and should have no place in their country’s insurance industry, especially at that stage in its development when numerous other client-friendly options were available. To address major problems, the Ministry of Finance held an insurance council on February 1, 1977, and promulgated “measures to modernize the insurance industry” that included a life insurance risk guarantee fund to ensure the solvency of insurance companies and an independent Insurance Dispute Review Committee to protect insurance subscribers.43 New regulations were placed on the asset management of insurance companies to curb excesses, but these regulations were largely inadequate. The nation’s strong modernization drives customarily relied on existing male-dominated functions of social networks that closely connected to the exchange of favors among corporate management, politicians, and government. In contrast, the success of individual insurance sales reconfirms that the individual-level network operated as crucially as the corporate-level one.

The increasing number of women in the insurance industry reflected a noticeable shift from group/corporate to personal insurance starting in the early 1970s. Until the 1970s, group insurance policies and corporate clients represented 70 percent of all life insurance subscriptions,44 which meant that profitability depended on the success of the group insurance market. To significantly increase corporate sales, insurance companies offered rebates to corporate clients, a dubious practice that spread rapidly throughout the industry, becoming commonplace among insurers by the 1960s.45 These practices proliferated so much that they accounted for the majority of operating expenses, so the operating expenses were generally understood as the cost for group subscriptions. In 1971, these problematic “operating expenses” (saeopbi) took up to 33.2 percent of total paid premiums.46 Industry insiders likened fierce competition for group subscriptions to “a war without shooting.”47 From 1972 to 1976, six life insurance companies even attempted to consolidate into one firm to dominate the group insurance market, reduce competition, and curtail the practice of giving corporate clients rebates that cut deep into company profits, but were unable to realize their plan.48

When group subscriptions fell precipitously from 70 to 24 percent of overall sales in the mid-1970s,49 insurers had to increasingly rely on individual subscriptions and the female agents who sold them. From 1973 to 1977, the phenomenal sales performance of female agents fueled an astonishing 142 percent annual growth in personal life insurance sales, whereas the group life insurance market accounted for only 36.4 percent.50 Putnam claims that women are much more skilled than men at applying social capital (Putnam 2000, 95); female agents not only validated that point but also had an advantage because many types of personal insurance came under the purview of women, mothers in particular. For example, mothers made decisions regarding education insurance subscriptions, because they were primarily responsible for overseeing their children’s education. Female agents were far better at developing mutual trust and building rapport with mothers and other female clients than male agents were.

As individual sales became the major revenue source, insurers tried to forgo female agents’ working-class image by recruiting middle-class women. Women, whose elite social status could burnish the reputation of an insurance company, fared better. For example, widows of prominent public figures, politicians, or powerful businessmen were scouted and preferentially hired because they brought ample social cachet to their employment.51 This change also reflected the demand for professionalization, which attracted middle-class women and raised more employment competition among women. The idea of jaa silhyeon (self-realization) was promoted by the industry to entice middle-class women, housewives in particular, and thereby expand its labor pool beyond poor and working-class women. For instance, Hwang Gwi-sim, a middle-class housewife, related her story in the 1984 issue of Saenghyeop. She had had a wonderful and fulfilling career as a schoolteacher but was forced to resign when she married; losing that meaningful career was bitterly disappointing for her. Unfortunately, hers was not an isolated experience for the practice of firing female employees once they married was widespread in South Korea at that time and rested on the patriarchal assumption that women no longer needed to work after marriage because their husbands took on the role of breadwinner. Although Hwang longed for the fulfillment her teaching career had given her, it is clear from her testimonial that she had also internalized prescriptive notions of womanly behavior embedded in the postwar ideology of hyeonmo yangcheo (wise mother, good wife) that expected a married woman to devote herself to caring for her family and skillfully managing a modern home. Yet a job as an insurance agent combined positive aspects of her previous teaching career—self-fulfillment and contributing to society in a meaningful way—with the ability to fulfill her domestic duties.

Sometimes, there was an emptiness that my husband and children could not fill… [I missed teaching, which was] another world lost to me. However, it was the insurance agent job which made me realize that a woman’s true identity comes from protecting hearth and home. I found work that fostered self-realization and let me contribute to society, yet I could still remain faithful to my home life [italics added]. (G. Hwang 1984, 44)

Like her former teaching job, she felt fulfilled while working as an insurance agent and believed that she was making a positive contribution to society. She also consciously chose insurance work because its flexible hours allowed her to balance work and her role as a “wise mother” and a “good wife.”

As more and more women entered the insurance business, motivated by the satisfaction to be gained from that work, their desire for a successful career along with decent wages intensified. To motivate valuable agents, insurance companies began to reward them in other ways. They held annual “queen contests” with prizes awarded to those with the best sales record for that year. Samsung Life Insurance, for example, held an awards ceremony (Fig. 2) to celebrate the achievements of its top three female agents: each queen, dressed in an evening gown and sparkling tiara to mark the occasion, proudly holds her award aloft and wears an elaborate flower garland given to her by the company; “warrior champions” (jeonsa chaempieon), a further accolade for these top-performing agents, is emblazoned on the back wall. The rhetoric of “warrior” in this context is intriguing. As Seungsook Moon explains, “militarized modernization” functioned to create “duty-bound nationals” and utilized male conscription for industrialization and economic development. “Militarized violence” continually penetrated the society (Moon 2005, 9), but treated women as “a secondary workforce” with reproductive responsibilities for dutiful nationals and household economic managers (Moon 2005, 78–93). Likewise, life insurance companies bestowed that accolade to inspire female agents to fight like warriors to increase sales and company profits. That term resonates with male “industrial soldiers” (saneop yeokgun) (Moon 2005, 139), revealing that corporations embraced the way authoritarian regimes disciplined the public and applied it to the female agents who were no longer a secondary workforce in the insurance industry.

Such elaborate awards ceremonies that happened once a year, stood in stark contrast to the daily disciplining of female agents that occurred within company offices, out of the public eye. Every morning branch offices held a morning assembly that was in effect a disciplinary ritual: the top saleswomen were announced, new sales goals were chanted, and everyone was expected to enthusiastically applaud the proceedings. All of that was designed to foment jealousy between female agents which, companies hoped, would translate into heightened competition among agents to increase sales.

Successful female agents commonly cited audacity, persistence, and diligence as key to their success rather than marketing strategies or in-depth knowledge of policies,52 and claimed that any agent who emulated them would experience similar success. They also gave advice about how to convince recalcitrant new clients to purchase a policy. Eventually, if the agent were persistent and diligent enough, even the most hesitant of clients could be convinced to subscribe. On average, ten to twenty visits53 were needed to win over a new client through gaining their trust, showing sincerity, and building rapport (Kwon 1984, 40). Dramatic stories were recounted about clients who had reluctantly purchased a policy and then unexpectedly got into an accident or were diagnosed with cancer; the policy they had been so hesitant to acquire ended up saving them and their families from paying exorbitant hospital fees. Or upon the sudden death of a husband, the family received a substantial insurance payment (Kwon 1984, 40). Enthusiasm replaced hesitancy: families appreciated that the agent had solicited the insurance subscription and emphasized the merits of insurance to friends and family, even introducing them to their agent.

Female agents with excellent performance records were promoted, becoming team leaders or managers who, in turn, hired new agents and formed their own teams that helped other women by giving them jobs. For example, Jang Yeong-hong managed policies and collected insurance premiums for 120 households each month and was well-compensated for that work, receiving a monthly salary of one million won. When she was promoted to a managerial position, she was allowed to hire her own team members according to the company’s recruiting system. So, she filled her team with new female employees (Saenghyeop 1983). Because senior agents like Jang helped other women by recruiting them, the insurance profession supported women’s overall social advancement. In other ways, however, that same industry exhibited considerable bias against women, promoting them only to the lower echelons of management. Highly critical of the insurance industry and its discriminatory practices, O Gyeong-ja, secretary-general of the Korean National Council of Women, pointed out this glass ceiling saying, “The insurance industry absolutely depends on its [large] workforce of women but a ‘pyramid structure’ keeps women from being promoted to high-ranking positions. That blatant job discrimination could cause female agents to leave the industry” (O 1983, 35).

Competition in the insurance industry became fierce as foreign insurance companies entered the South Korean market. Although female agents contributed to individual insurance sales growth to make them the largest revenue source for insurance companies, the feminization of insurance sales shows mixed outcomes. On the one hand, despite insurance sales attracting a high number of female employees, systemic gendered hierarchies in the division of work, wage, and promotion in the insurance industry did not improve significantly. On the other hand, young, unmarried female agents’ increasing advances in individual insurance sales solidified the fixed image of married female agents as old, dependent only on their social networks, and thus unprofessional. The reduction of solicitation subscriptions to female agents’ sales methods easily blindfolded many other complicated situations in the insurance industry that this article has discussed. This simplified view inside the industry is well-reflected through the remarks of Hwang Chang-gi, head of the Insurance Supervisory Service in 1993. After meeting with major insurers’ presidents, he said to reporters that “it is desirable to switch to male employees or young women rather than married women to foster professionalism in insurance sales.”54 This approach to hire young employees separated insurance agents by their age, deepened the age divide among female agents, and reinforced the images of the existing older female workforce as unprofessional. The age divide among female agents did not apply to their male counterparts, and instead naturally perpetuated the gender divide by binding male employees or young women together as one group in a new central workforce. This regression simultaneously negated the merits of social networks and mutual trust as sales strategies.

Because South Korea’s authoritarian regimes failed to provide an adequate welfare system, ordinary citizens had to find ways to sustain their own wellbeing and security, a situation ripe for the burgeoning development of the insurance industry, which featured solicitation subscriptions whose success relied on mutual trust and reciprocity between insurance agent and client. Female agents, in particular, capitalized on interpersonal skills to facilitate solicitation sales. Those skills, along with tenacity and hard work, resulted in incredible sales figures that fueled the astonishing growth of the South Korean insurance industry from the 1960s to the 1980s; by 1982, it was 11th in the world in terms of global life insurance orders (Saenghyeop 1984b). Amidst such unprecedented success, high rates of cancellation and staff turnover, especially among female agents, suggest that the industry’s practice of putting extreme pressure on female agents to increase solicitation sales depleted the mutual trust and social capital those agents relied on to succeed, which caused customers to cancel policies and agents to resign in frustration, the latter unfairly perceived as overbearing and unprofessional. After dominating insurance sales for decades, the tide turned against female agents when male agents re-entered the field from the late 1990s onwards to work primarily for foreign insurance companies. Not surprisingly, male agents’ reputations did not suffer the same scurrilous attacks as those of their female counterparts; instead, they were perceived as highly professional, akin to financial consultants.55 Insurance sales may have reverted to masculinization, but that shift in the 1990s can introduce an important question about whether this will revive male-centered networks in South Korea’s capitalism or whether it will signal an effective gender-neutral (or even genderless) business model within the insurance industry.