Seoul, the capital of South Korea, is often described as a place where one can appreciate both modern life and traditional culture. The existence of traditional culture in Seoul is most dramatically visualized with traditional architecture surrounded by a wall of skyscrapers. Royal palaces in Seoul are exemplary sites for such traditional aspects of metropolitan Seoul. The traditional architecture of royal palaces, combined with their visitors wearing rented traditional Korean clothing called

Seoul was the national capital throughout the entire period of the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) and it has four major royal palaces: Gyeongbokgung, Changgyeonggung, Changdeokgung, and Deoksugung. These palaces have greeted people from the world over, but as famous tourist spots they have long been mainly associated with foreign visitors. In recent years, however, there have been changes ticed in the ratio of visitors, with the number of Korean visitors steadily increasing. A major contributing factor in the increase in domestic visitors was the nighttime events introduced in 2010. But prior to the nighttime opening of the palaces, other forms of tourist programs situated in royal palaces attracted visitors, the changing of the royal guards ceremony being one of them.

The changing of the royal guards was initiated in 1996 at Deoksugung by the Seoul Metropolitan Government. A very similar ceremony was then launched at Gyeongbokgung in 2002 by the Korea Culture Foundation. While the royal guards changing ceremony is a good example of a popular tourist program featuring royal palaces, this program does not involve the active participation of visitors as much as does the nighttime opening. While a nighttime visit requires competitive booking in advance, the royal guards changing ceremony does not operate on a reservation basis, being open to any passer-by who wishes to view it; many of the spectators “accidentally” attend the program with little knowledge of its content or schedule (J. Kim and S. Park 2005, 76–77). Setting aside the lack of historical accuracy in the reconstruction of the ceremony itself and the traditional attire of the royal guards (Bang 2014, 27), the royal guards changing ceremony cannot compare with nighttime opening space-wise, in that it takes place in front of the main gate of royal palaces, and does not necessarily attract visitors to palace grounds.

The new-found interest in royal palaces among Koreans is largely from young people, who found in nighttime openings a refreshing form of late-night entertainment. And unlike the royal guards changing ceremony, where supposedly traditional cultural representation is unilaterally offered as a tourist performance (Kang 2010), nighttime opening provides a platform on which various intentions and expectations can be projected. It is not difficult to find testimonial postings on social media about nighttime visits to the royal palaces. The media and the Office of Cultural Heritage Administration have interpreted the popularity of nighttime openings among the domestic audience as a significant sign reflecting renewed interest in national identity and traditional culture.

This article argues against such simple readings of the popularity of nighttime openings at royal palaces and attempts to examine the practice and perception of this particular cultural event at the intersection of history, memory, and identity. Based on the author’s observations at nighttime openings, this article examines the process in which past experiences, especially that of Japanese colonial rule, are reconfigured through historic nostalgia and amnesia in reconstructing the physical as well as emotional parts of royal palaces. This article also examines the controversy concerning the propriety and authenticity of hanbok and the upscale nighttime opening programs to illuminate identity politics and the class-conscious consumption of tradition. What the following sections illustrate is how royal palaces are sites not just for the formation of a seamless collective memory, but for the contestation and divergence of desires and identities.

Historical Nostalgia and Heritage Tourism

Once recognized as a pathological symptom of a mental disorder (Jackson 1986; McCann 1941; Rosen 1975), nostalgia has come to be understood in a new light in the fields of history and the social sciences (Havlena and Holak 1991; Kaplan 1987; Sedikides et al. 2008). Although nostalgia was once viewed as contributing to depression, and thus requiring medical treatment, recent studies interpret nostalgia in light of cognitive processes and psychological outcomes. Nostalgia on the collective level in particular has gained attention, and its relationship with group identity has been a focus of interest. For example, national nostalgia can contribute to the formation of optimistic group orientation (Smeekes 2015). Historical nostalgia, which is often related to the politics of collective memory, is about a longing for the past when reflecting on positive reminiscences (Boym 2002; Goulding 2001). Drawing on Christou et al.’s conceptualization (2018, 43), Chark (2021, 3) defined historical nostalgia as encompassing “the desire to return to a past not experienced by the individual yet believed to be superior to the present.” Historical nostalgia consists of selectively collecting fragments of bygone days to reconstruct history, often in idealized and comforting ways, to counteract the contradictions experienced in the present tense (Creighton 1997, 251–252). Books, film, public education, and media have their roles in insinuating the representation of a given past to those who had no experiences of it (Holak et al. 2007; Stern 1992). Memory is based as much on forgetting as remembering, and in the case of collective memory, representations become far more crucial than the actual events of the past. Historical nostalgia may enable rosy representations of the past, and representations of the past beget romantic obsession and serene delusion. In this dialectic process, the idea of authenticity provides both motivation for and confirmation of appreciating the reconstructed legacy of the past (H. Kim and T. Jamal 2007). It has been pointed out that authenticity has different dimensions, and the process of forming authenticity is explained as “authentification” (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Bruner 1992, 304).

In tourism, heritage destinations are exemplary places where authenticity, historical nostalgia, and representation of the past intersect. People visit and become connected to heritage sites through nostalgic emotions guided by the idea of authenticity. At heritage destinations, representations of the past meet the desires and experiences of visitors, cultural property custodians and organizations, and government. In domestic heritage tourism, in particular, representations infused with historic nostalgia become powerful sources for in-group identity (Chark 2021). The idyllic image of the past obliterates present struggles and conflicts by evoking the

Royal palaces in South Korea have been mainly discussed in the context of traditional aesthetics, historical tragedy, and national identity. As signature cultural heritage destinations of South Korea, the main target audience of royal palaces has long been foreign visitors and an international audience. Unlike in domestic heritage tourism, for foreigner visitor-focused tourism historical nostalgia is largely irrelevant as the foreign audience views these places in terms of exotic encounters. For domestic audiences, on the other hand, both nostalgia and amnesia are at play to create a smooth narrative about identity and tradition. In particular, nighttime openings at the royal palaces unveil the process by which colonial traces are either muted or highlighted to better entwine with the sense of belonging and national spirit.

There have been a limited number of studies on royal palaces in Seoul, and the majority of these have understood royal palaces in an objectified way by mainly discussing marketing strategies, consumer behavior, and satisfaction analysis associated with heritage tourism (J. Kim and H. Lee 2009; Olya et al. 2019; S. Park and S. Kim 1998; Yu 2006). Analyses of nighttime tourism surrounding cultural heritage sites are mostly of this vein. For example, Chen et al. (2020) examined “Cultural Heritage Night” programs in South Korea as a tourism brand and described the relationship between customer satisfaction and brand loyalty. Yim (2019) also focused on ways of enhancing consumer perceptions of the value of cultural heritage in Cultural Heritage Night programs. In these studies, royal palaces exist as a given background that exude seamless traditionality. Seldom examined in such investigations is how traditionality is reinterpreted and redefined by tourist programs at royal palaces.

There are several studies on the topic of heritage tourism in Korea that discuss issues such as power dynamics and the role of authenticity (Cohen 1988). Timothy J. Lee et al.’s study on the development of heritage tourism in Korea (2010) applies structural analysis to elucidate the dynamics of conflict and collaboration among different parties in heritage tourism projects. The notion of authenticity has been explored to show its diverse forms in representation and implication. Based on survey data collected among visitors to Hahoe village in Andong, South Korea, Eunkyung Park et al.’s survey study (2019) shows the relationship between different dimensions of authenticity and visitor intentions to revisit. Based on objective, constructive, and existential perspectives of authenticity, Park et al. argue that authenticity is achieved differently based on the visitor: either through original items, through imagery and expectation, or through tourist activities. In a similar vein, Hwang Hee-jeong and Park Chang-hwan (2015) also argue that authenticity is constructed and changes based on a tourist’s experiences and perceptions.

As Korean heritage tourism has been mostly examined through satisfaction evaluations with marketing implications, little research attention has been paid to the topics of identity politics at heritage sites. Park Hyung yu’s studies on heritage tourism are a few exceptions to this trend. Park viewed heritage as cultural production and examined how the past and heritage are perceived and appropriated in maintaining national sentiment and solidarity (H. Park 2010). Based on tourist surveys at two royal palaces, Park argues that heritage tourism can create a place where the colonial past is reconstructed, which reveals the ambivalent nature of colonial heritage (H. Park 2016). While Park’s works are insightful in illuminating the complex dynamics of heritage, nationhood, and the colonial past, her analyses focus on how heritage settings have conditioned and encouraged local tourist perceptions and interpretations of the past. While Park’s work is more focused on the influence of heritage tourism on visitors, this article is more interested in the ever-constructed nature of heritage tourism. Hence, this article attempts to go further by presenting how heritage tourism is propelled by collective identity as well as consumed with individual desire, and how heritage tourism sites become the location for dynamic contestation in terms of identity, memory, and aspiration.

Snapshots of Night Fever at Royal Palaces

On the evening of March 1, 2016, Changgyeonggung, one of the royal palaces of the Joseon dynasty, welcomed 2,500 visitors who had gathered for a nighttime opening. The front gates of the royal palace were set to open at seven o’clock, but even before the opening time the visitor line already stretched for over 100 meters. The nighttime opening of royal palaces began with Gyeongbokgung in 2010. At first, this was designed as a one-time event to celebrate the G-20 Seoul summit. But it turned out an unexpected success, especially among South Koreans, and this enthusiastic response by domestic visitors resulted in nighttime openings becoming a regular feature over the following years.

The venues for nighttime opening programs are three major royal palaces of the Joseon dynasty: Gyeongbokgung, Changgyeonggung, and Changdeokgung, all of which were once occupied by Joseon kings and royal families. Tickets for these nighttime openings can only be purchased online at two designated sites. A limited number of on-site tickets are available, but they are reserved exclusively for senior citizens and foreigners (two groups considered less familiar with using Korean online purchase systems). The online ticketing system usually opens a couple of weeks prior to the given night opening. The dates for nighttime openings have increased as their popularity has soared, and in 2016, royal palaces greeted night visitors over four different periods, each continuing for 30 nights, rendering a total of 120 nights that year. Considering that a total of 48 nighttime openings were held in 2015, this huge increase testifies to the high public interest in this event. In 2016, every opening night accommodated around 2,500 visitors and the online system sells tickets for one period (30 days) at a time. For example, the online ticket system for the period March 1–April 4, 2016, opened on February 24 at 2 p.m., and all 75,000 tickets for this period were sold out within two minutes. Those who had secured tickets showed off their achievement on social media, while others who failed grudgingly demanded more open nights. After 2016, the Office of Cultural Heritage Administration continuously expanded its nighttime opening programs and as of 2019, Changgyeonggung is open at night year-round.

The popularity of this event was, as mentioned above, truly unexpected. As the initial design of the event clearly indicates, royal palaces have long been attractive to international tourists, but not so much to a domestic audience. Royal palaces were considered as embodying traditional values that would appeal to tourists, but would not appeal to a domestic audience whose interests were assumedly more geared towards modern life. During the 1990s and early 2000s, royal palaces were thus regarded as must-see spots for foreign visitors to Korea: large tour buses lined up outside the royal palaces to load and unload tour groups. The South Korean government and the Office of Cultural Heritage Administration promoted royal palaces to foreigners as places where one could truly appreciate the essence of traditional Korean culture and aesthetics through architecture, spatial arrangements, and court gardens.

Starting in the early 2010s, there was a noticeable change. Royal palaces are still major tourist spots for foreign visitors, but at the same time, more and more Korean people file in.

Anticolonial Spectacle at Gyeongbokgung and the Coming of Modern Cultural Heritage

Among the three royal palaces mentioned above, Gyeongbokgung has garnered the most attention in terms of Korea’s colonial experience. Built in 1395 as the main palace of the Joseon dynasty, Gyeongbokgung was the residential palace of Joseon monarchs until it was completely burned down during the first Japanese invasion of Korea (1592–1598). Following this, both Changgyeonggung and Changdeokgung were elevated to the status of main palaces until Gyeongbokgung was rebuilt and expanded (1865–1867) by the Heungseon Daewongun, the father of King Gojong (r. 1863–1907). However, following Japanese annexation of Joseon in 1910, many buildings in Gyeongbokgung were demolished by the Japanese, some of the demolished materials being used to renovate other palaces, mansions, and restaurants, or even sold and shipped to Japan to decorate the mansion of a high official (D. Kim 2007, 90–91). More significant destruction of Gyeongbokgung by Japan came in the following years as the Japanese razed dozens of royal buildings within Gyeongbokgung precinct to construct the headquarters of the Government-General, the Japanese governing authority in Korea (Yoon 2001, 293). The Government-General building was built in the heart of Gyeongbokgung, and the majority of South Koreans believe that the Japanese imperialists had the deliberate intention of “repressing the national spirit of Korea” (Yoon 2001, 282) by carving out a colonial headquarters within the heart of the royal palace of Joseon.

After liberation, the former Government-General building was continuously at the center of heated debate. On the one hand, many Koreans could not stand the fact that such a blatant symbol of Japanese colonialism still stood so robustly in the heart of their capital city and argued that it should be demolished forever. People on this side of the debate often pointed out the fact that the building was regularly visited by Japanese students on school trips and other Japanese tourists coming to South Korea, which was often interpreted as an exemplary case of colonial nostalgia (see Bissel 2005). On the other hand, many people, including historians and architects, insisted the building be preserved because it contained undeniable historical and architectural value (see M. Park et al. 1995; B. Kim 2007; D. Kim 2007; Son and Pae 2018). Some historians also pointed out that the Government-General building had national value as well (Yoon 2001, 299–303; D. Kim 2007, 116–118). The building was occasionally used by the South Korean government after independence for hosting historical events, such as the opening of the Constitutional Assembly, the promulgation of the Constitution, and the inauguration of the first South Korean president Syngman Rhee (1875–1965) (H. Jung 2018). As a compromise, some architects and historians recommended removing the building from the Gyeongbokgung area, but nonetheless suggested the building not be torn down due to its architectural quality and it embodiment of Korea’s historical experiences.

On the destiny of the former Government-General building, President Kim Young-sam (1993–1998) appeared to be determined to put an end to this issue during his presidency. He announced that destroying the former Government-General building was a way to “recover our national pride and national spirit.” He stated that “it would be remembered as a significant moment for correcting our distorted history for a better advancement to the global era” (Ministry of Culture and Sports 1997, 341–344; National Museum of Korea 2006, 34). Although several civil committees mobilized against the government decision, the dogmatic sentiment of

Finally, on August 15, 1995, during a celebration marking the fiftieth anniversary of independence, the former Government-General building was ceremoniously demolished. While the side wings of the building had already been demolished a few weeks previous, the main part of the building with its distinctive dome and pinnacle top still stood intact. In preparation for the ceremonial flattening, the pinnacle top weighing over twenty-five tons had been cut into two pieces, a metaphor for the destruction of Japanese colonialism. After a series of routine protocols, the pinnacle top was finally removed by a 300-ton crane, amidst steamy summer heat and industrial dust, and to the cheerful applause of the 50,000 guests and spectators. Due to safety and efficiency concerns, only the upper part of the two sections was pulled down. Nevertheless, as many healing ceremonies do, this ceremony seemed to give some South Koreans peace of mind. One person who was in charge of the destruction process told the press afterward that the ceremony was followed by a sudden shower (which is not unusual in August in South Korea) that poured down only within the Gyeongbokgung area, while right outside the palace area there was bright sunlight (which is not usual given the geographical proximity). He interpreted this phenomenon “as if the traces of Japanese colonialism were destined to be wiped away.”

The symbolic meanings of the agenda-building process around the razing of the former Japanese Government-General building has been analyzed by political scientists (Ha 2011; Y. Park and S. Jang 2017). The debates around the fate of the former Government-General building reveal not only the clash between colonial and national, but also the fraught encounter between memory and representation. When the plan of housing the National Museum of Korea in the former Government-General building was announced in 1982 by the South Korean government, it was interpreted as “having a crucial meaning of cleansing the Japanese colonial remnant with the sense of national sovereignty” and as “answering the Korean people’s [nation’s] request” (H. Jung 2018, 205–206). Thirteen years later, however, the same building was understood not so much as a showcase of nationalistic determination as a persistent symbol of the nation’s difficult history of colonization.

Even after the structure’s physical disappearance, the former Government-General building continues to be a referential point in addressing the process by which colonial legacy and postcoloniality is configured in Korea over time. While the year 1995 witnessed Korean society’s firm rejection of colonial architecture, which resulted in the total annihilation of the former Government-General building, the ensuing 2000s saw the development of a rather different social attitude towards buildings and facilities from the colonial period. Colonial architecture and landscape gained attention of a different sort with the introduction of the concept of “modern cultural heritage” (

The development of an urban revitalization policy, heightened interest in tourism resources, increased interest in the value of modern heritage, the emergence of provincial governance, and changed perspectives on colonial-era heritage all contributed to generating new perspectives toward preservation and even the active utilization of the cultural heritage inherited from the colonial period (Son and Pae 2018, 23). While the destruction of the former Government-General building in 1995 manifested the predominant discursive power of nationalism, the concept and institutionalization of modern cultural heritage in the 2000s signaled the emergence of cultural consumerism and diverging voices around the colonial imprint in Korea (Moon 2011, 267–273; Choi 2021; H. Park 2021), As Jaeho Jeon has pointed out, the destruction of the former Government-General building had the ironic effect of expanding the concern with and discussion around the preservation of colonial architecture (J. Jeon 2020, 113). With the backdrop of the anticolonial spectacle of the destruction of the former Government-General building and ensuing social discussion of the utilization of modern cultural heritage, what truly shapes Gyeongbokgung as a site of memory is a collective sense of ambivalence towards colonial modernity and nationalist sensibility (see H. Lee 2021).

The Reconstructed Memory of Royal Palaces

The removal of the former Government-General building accelerated the restoration project of Gyeongbokgung that began in 1990, the main goal of which was to restore the palace to its pre-colonial state, which is often called its

The first stage of the current restoration project was completed in 2011, and the second stage is scheduled to be finalized in 2030. The eventual purpose of this project is “to promote the excellence of [Korean] national culture and to use [Gyeongbokgung] as a source for history education and culture-tourism” (Office of Cultural Heritage Administration 2011). It is undeniable that the removal of the Government-General building and the restoration project succeeded in renewing the general public’s interest in Korea’s royal palaces. However, interpreting the increase in domestic visitors to royal palaces as evidence of heightened nationalist consciousness misses an important point. In other words, even though the number of domestic visitors increased over the past years, the way they consume the meanings of the royal palaces is not always congruent with the current master narrative of South Korean society, which focuses on anticolonial and nationalistic sentiments.

As noted above, most visitors to the nighttime openings of the royal palaces are young couples. I attended nighttime openings on five different occasions between 2015 and 2019 and made close observations among the crowd. To most visitors, it seemed that the history or traditional authenticity of the royal palaces were not of much interest. People were busy taking photos of themselves with selfie sticks, while some couples preferred to cuddle in the corner of buildings. Even if some visitors were eager to learn the architectural and historical details of the buildings from the nearby information boards, they were nearly impossible to read as there is no lighting installed for them. Visitors as well as the media exhibit a strong tendency to relate the popularity of nighttime openings to a rediscovered interest in national history and tradition, but the tradition is being consumed on a rather superficial level—as one newspaper expressed it in an aptly titled (though perhaps not realizing its possible sarcastic nuance) article, “Let’s Take a Relaxing Night Walk in the Palace Courtyard as if We Were Kings.”

Even the colonial experience on the part of Koreans is very selectively remembered and reinterpreted, pendulating between nostalgia and amnesia. The whole restoration project is based on the criticism that Japanese colonialism fundamentally tainted and ruined the royal palaces and, by extension, Korean national spirit and pride. Erecting the colonial headquarters in the heart of Gyeongbokgung is considered one of the many malicious acts perpetrated by the Japanese. Another infamous example directly related to the Joseon royal palaces is the Japanese degradation of Changgyeonggung. In 1911, one year after its annexation of Joseon Korea, Japan removed several buildings within the grounds of Changgyeonggung to accommodate a public zoo (the first in Korea) and botanical garden. The Japanese authorities then changed the name of Changgyeonggung to Changgyeongwon (

The dominant narrative in South Korean society has long emphasized a fundamental discontinuity between the Japanese colonial period and the post-liberation era. While Gyeongbokgung and Changgyeonggung are now being restored under the banner of “redressing colonial history and reestablishing national spirit” (Ministry of Culture and Sports 1995, 108), the sentiment of which seems to be reinforced by the general public’s desire for an authentic experience of traditional Korean life by visiting royal palaces, how royal palaces are being consumed by domestic audiences markedly resonates with the use of Joseon royal palaces during the colonial period: in both cases, royal palaces were promoted as places where the public might have a sense of sharing in royal life and enjoy nightly leisure time. The interesting point here is, although contemporary South Korean society is eager to stand upon the antipode of the Japanese colonial period, nighttime openings exhibit a nuanced similarity with

With the current restoration project of Gyeongbokgung standing as an antipode to Japanese colonial defamation of Korea, public memory easily ignores the post-independence deterioration of the same place. During the 1960s, many parts of Gyeongbokgung continued to be destroyed to accommodate military facilities and the rapid development of Seoul (D. Kim 2007, 122). Until 1968, when the Pak Chung-hee government began to locate the source of modernization in the national spirit, Gyeongbokgung and other royal palaces were mostly considered and utilized as places for entertainment rather than of traditional values. It has been pointed out how the Japanese colonial government’s use of Gyeongbokgung as site for the 1915 Industrial Exposition to celebrate its successful five years of ruling Korea had the effect of denying royal authority as well as physically and symbolically redefining the spatial arrangement of the palace (Oh 2020, 151). Interestingly, the Pak Chung-hee government also held an industrial exposition at Gyeongbokgung in 1962 to celebrate the first anniversary of its successful military coup (Yum 2022, 913). It had the similar effect of destroying as well as rearranging many parts of the palace grounds, but there is far less public knowledge of this in discussions of Gyeongbokgung’s past trials.

Also noticeable is that with the heated popular interest in nighttime openings over the past few years, it is often forgotten that during the period 1984–2011, quotas on daily visitors were considered one of the best ways of protecting the original state of the royal palaces (Hashimoto 2016, 162–173). The royal garden of Changdeokgung (colloquially referred to as the ‘secret garden’), for example, was for long time a highly restricted area for public visits on the grounds that visitor numbers would damage the palace (Yoon 2001). Today, this garden offers an upscale nighttime program called the “Moonlit Promenade.” Hence, it is worth noting that there is a discontinuity in South Korean society’s own perceptions of and practices around royal palaces. It also bears pointing out that the physical removal of the colonial legacy might be a necessary step for a postcolonial state like Korea, but that does not mean the discontinuity or absence of lingering effects. Todd Henry aptly noted this point in his book on the postcolonial landscape of the royal palaces in Korea, noting how “erasing the physical remnants of Japanese rule…will not necessarily silence the historical memories that continue to haunt these hypernationalistic sites” (Henry 2016, 217).

Reinterpretation of Tradition and Negotiation of Identities: Hanbok-wearing at Royal Palaces

Until 2013, free admission to royal palaces was granted to those wearing hanbok on special dates, including Lunar New Year’s Day and Chuseok (Korean Thanksgiving Day). On such occasions, people wore their own personal hanbok to these events and the number of such visitors was few. Changes came when in 2013 the Office of Cultural Heritage Administration initiated free admissions for hanbok wearers (Jeon and Sung 2017, 81–82) year-round. According to the Office of Cultural Heritage Administration, this campaign was designed to promote the popularization and globalization of hanbok. Once free admission for hanbok wearers was made year-round, hanbok-rental stores burgeoned near royal palaces to attract visitors with double benefits—free admission and experiential entertainment.

Studies have shown that wearing hanbok in and around royal palaces increases visitor satisfaction and positive memories by heightening feelings of collectiveness and belonging to the site and the atmosphere (K. Lee and H. Lee 2019; J. Kim 2019, 71–72). Jeon and Sung’s study (2017) on hanbok wearers and their preferred destinations revealed that Gyeongbokgung was considered a playground for “hanbok trippers” because its traditional landscape offered attractive background for photos. In addition to the entertainment aspect, there exists also a ritualistic element. As wearing particular attire in rites has the effect of demarcating the sacred from the profane, wearing hanbok in royal palaces helps visitors appreciate the heritage site as a liminal space where the order of normal life is suspended and a new identity can be formed, thus offering visitors an “escape experience” (M. Kim 2021, 202–203).

As the popularity of wearing hanbok in royal palaces grew, rental shops soared in number (S. Park and M. Lee 2019, 76), and the design and materials became bolder and flashier to attract visitors. Hanbok at such rental shops are usually made of colorful fabrics adorned with glittering details and laces, complete with fluffy petticoats and embellished hairpieces. Since these hanbok have different cuts, adornment, and color tones from traditional ones (M. Kim and S. Kim 2020), they are also called fusion hanbok or modern hanbok. While fusion/modern hanbok were popular among visitors around royal palaces and other tourist destinations, concerns and criticisms were also raised that such “inauthentic” hanbok deteriorated the traditional aesthetics of hanbok (M. Kim and S. Kim 2020, 656; Yoo and Chang 2021, 187–188). In her study on market changes in rental hanbok, Shim (2017) showed that consumers understood recent “experiential hanbok” as akin to stage costumes, clearly distinguishing them from ceremonial hanbok. Mira Kim’s interviews with Korean consumers of rental hanbok also showed that the appeal of fusion/modern hanbok derived from its perceived exoticness and how its flashiness stood out well in photos, which were regularly uploaded on various social media (M. Kim 2021, 221–222). The popularity of hanbok at royal palaces and similar heritage tourist sites thus reveals the desire for self-presentation and experiential entertainment among individual visitors rather than any raised consciousness of traditional culture (J. Kim 2019, 65–67; M. Kim and S. Kim 2020, 659; Park et al. 2019, 1434).

Proponents of fusion hanbok around royal palaces as reinterpreted tradition have argued that the popularity of fusion/modern hanbok, especially among foreign tourists, would ultimately enhance global attention on Korean culture (J. Kim 2019, 73; J. Lee 2017; 448). Others have warned against the degradation of tradition and loss of cultural identity.

The free admission policy for hanbok-wearing visitors to royal palaces stirred up gender-related identity politics as well. The Office of Cultural Heritage Administration posted in FAQ on their website about the types and forms of hanbok eligible for free admission. Initially, the Office of Cultural Heritage Administration provided guidelines stating either traditional or fusion/modern hanbok was acceptable as long as they followed basic forms of hanbok: it is a set of top and bottom and tops should have collars and wrapping parts. The guidelines on proper hanbok also emphasized in red that men and women should wear hanbok gender-accordingly: men should wear men’s tops and trousers, and women should wear women’s tops and skirts. A group of transgender and human-rights advocates contended that such guidelines violated the rights of some and that it consolidated the conventional idea of distorted gender roles.

Back in February 2007, with the global popularity of the Korean Wave, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism had announced a “Plan for Promoting Korean Style,” in which hanbok (along with the Korean alphabet, Korean traditional house, Korean food, Korean music, and Korean traditional paper) was designated as one of the six emblems of traditional Korean culture.

Consuming Tradition and Reproducing Class in Special Nighttime Programs

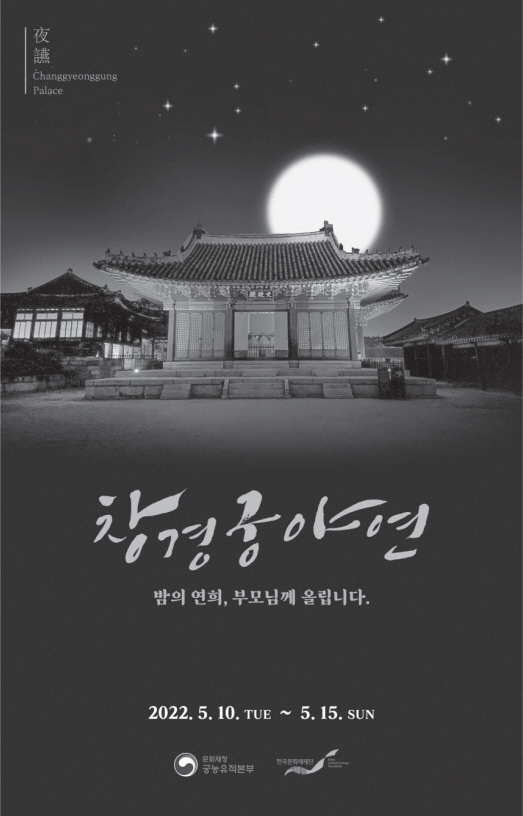

The nighttime opening programs at Seoul’s palaces have undergone changes over the past years. As mentioned above, it began at Gyeongbokgung and then was early on adopted at Changgyeonggung and Changdeokgung. As the program’s popularity soared among the Korean people, the Office of Cultural Heritage Administration designed and presented guided night programs with smaller groups of people and with much higher ticket prices. Examples include the Moonlit Promenade at Changdeokgung, Starry Night Walk at Gyeongbokgung, and, most recently, Yayeon (meaning night court banquet) at Changgyeonggung.

What Moonlit Promenade and Starry Night Walk intended to deliver is the feeling of being a member of Joseon royalty. Enjoying the royal palace at night gives visitors a sense of being selected for exceptional treatment, based on the fact that only a limited number of people are admitted to the royal palaces after normal operating hours. Special programs elevated this feeling to a higher level by allowing much smaller groups of people to have tours tightly guided by an entourage of reenacted court ladies. The Moonlit Promenade and Starry Night Walk programs include a special dinner while watching traditional music performed by artists wearing period-appropriate attire. The brochure explains that the dinner course is a careful reconstruction of Joseon kings’ meals with exceptional ingredients such as abalone, beef ribs, and rare mushrooms. Even the plates and utensils imitate those used at court.

The scene of a luxurious dinner to the accompaniment of traditional music provides an intense feeling of

Yayeon at Changgyeonggung shows how this particular form of consumption of tradition interweaves the desire for upward social mobility with the traditional virtue of filial piety. Launched in October 2021, this program is a reenactment of the night court banquet that Prince Hyomyeong (1809–1830) threw for his father King Sunjo (r. 1800–1834). Yayeon is different from the Moonlit Promenade or Starry Night Promenade programs in that the participants of this program are 10 families composed of senior parent(s) and their adult sons/daughters. In the reenacted Joseon banquet for the king (Sunjo), the parents play the role of Joseon aristocrats who are invited to the royal court banquet. To transform into their supposed roles of Joseon aristocrats, parents are fully dressed as such and even receive a full make-over prior to the program. During the program, the sons and daughters of the participants remain as audience members and watch the show in which their parents are treated with food and music by the king and prince.

The main theme for the Yayeon as advertised is filial piety, and it unfolds on two levels throughout the show. First, the program reminds participants how good of a son Prince Hyomyeong was to King Sunjo. During the performance, the prince reenactor reads a long letter of respect and gratitude to the king and pleases him with music and dance that were believed to have been composed by Prince Hyomyeong himself. With its historically based reenactment, this performance is also about the Confucian relationship between parents and their offspring who participate in it. The theme of filial piety is transported from the prince and the king to the real participants, as the former represents the latter. By having participants identify with the royal family, Yayeon confirms Confucian familial virtue as timeless and universal through what Urry articulated as the “tourist gaze” (Urry 1990). At the same time, the program satisfies the desire or aspiration of the participants for the highest social status. As noted in the program’s advertisement, “participating parents will fulfill the role of invited aristocrats, and they will experience special moments as the main guest of the royal banquet in the traditional attire of Joseon.”

While the discourse around royal palaces as symbolic places for tradition and cultural identity of Korea seems to generate a collective sense of Koreanness, special programs reveal the juncture where class consciousness intersects with traditional values. The reconstructed royal life presented in nighttime opening programs is a fragmentary patchwork, sewn with the thread of desire for distinction in Bourdieu’s sense. At royal palaces, tradition is endorsed to confirm collective identity, and at the same time it is consumed as “a fantasy of achieved upward mobility, and it has its favored models of the aristocratic good life” (Frow 1991, 147). The aforementioned controversies around hanbok and the perceived discontinuity with colonial experiences also present the complex process in which cultural, national, gender identities intersect with the landscape of history and tradition.

As places symbolizing the nation’s glorious past, Korea’s royal palaces are considered to embody the integrity of national history, traditional values, and national identity. The destruction of Korea’s royal palaces during Japanese colonial rule (1910–1945), such as by erecting the headquarters of the Japanese Government-General in the heart of Gyeongbokgung and establishing a public zoo in Changgyeonggung, is understood as a deliberate effort by Japan to repress Korean national identity.

Being a symbol of such oppression, royal palaces stand as a source of Korean identity and traditional culture. The tradition associated with royal palaces has long appealed to foreign tourists, but now nighttime opening programs provide a platform for Koreans to confirm their collective cultural identity as well as to redefine desire and self-presentation. On one hand, the narratives of national history and culture around royal palaces shape the collective identity of Koreans. On the other, night programs wrapped in traditional lifestyles and values infuse the participants with a sense of individual identity and social prestige, inspiring individual desire for distinction. As such, royal palaces have become sites for conformity as well as sites for divergence.

While the Korean people’s newly found appreciation of the country’s royal palaces is often understood as a renewed focus on traditional aesthetics and culture, such interest also shows how Korea’s colonial experiences have been reframed into nostalgic memory by way of historical amnesia. On one hand, South Korea’s pursuit of the original and the traditional demonstrates how nostalgic memory has enabled the perpetuation of what MacCannell (1973) called “staged authenticity.” On the other hand, South Korea’s strong aversion to its colonial experiences under Japanese rule manifested itself in silencing historical memories as well as evolving social meanings of its colonial encounter, revealing the historical amnesia in which Korea’s postcoloniality constantly reproduces itself.

While people visit royal palaces for entertainment, education, and the confirmation of a collective identity, this article has argued that royal palaces are also sites for the reconstruction and redefinition of memory as well as identity. As seen in the controversy around the authenticity and legitimacy of hanbok-wearing in royal palaces, the variegated configurations of identity politics are at play at the royal palaces. As royal palaces are believed to embody traditional culture, aesthetics, and values as well as national identity and history, it is crucial to note that visitors’ perceptions of and practices around royal palaces not only confirm and consume the dominant narrative on Korean history and culture, but also continuously redefine and reconstruct new meanings of tradition, heritage, authenticity, and identity.

This article is based on participant observations and a literature review. The exclusion of interviews with staff and visitors at the royal palaces is intentional: more often than not, interview questions employing such terms as tradition, national identity, and authenticity have the effect of delimiting the range and depth of interviewees’ responses, and rarely generate meaningful results. This is because the dominant discursive power of such topics has permeated Korean society through public education, official promotion, and media representations. Hence the absence of interviews in this article was a strategic choice, an attempt to avoid big-worded questions that might shape interviewees’ responses in tune with the dominant social discourse. Still, the author firmly believes that long-term, on-site fieldwork conducted with a focus on interview groups would significantly improve the depth of current research. In the future, interview-based thick descriptions and further research on generational and regional differences in consumer behavior and perceptions of tradition and identity will better illuminate the complex and dynamic aspect of the historic nostalgia associated with royal palaces.